NOW IN 22 DIFFERENT LANGUAGES. CLICK ON THE LOWER LEFT HAND CORNER “TRANSLATE” TAB TO FIND YOURS!

By Jeff J. Brown

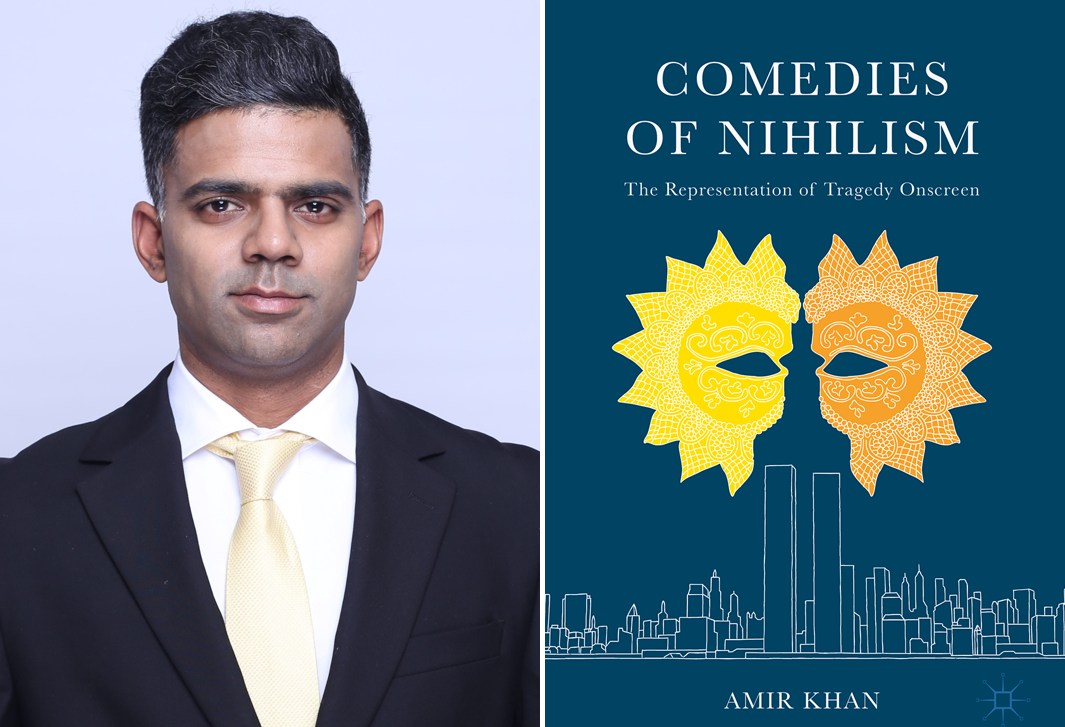

Pictured above: Amir Khan and his excellent book about cinema, “Comedies of Nihilism: The Representation of Tragedy Onscreen”.

Thousands of dollars are needed every year to pay for expensive anti-hacking systems, controls and monitoring. This website has to defend itself from tens of expert hack attacks every day! It’s never ending. So, please help keep the truth from being censored and contribute to the cause.

Paypal to je**@br***********.com. Bank cards can also be used through the PayPal portal. Thank you.

Do your friends, family and colleagues a favor to make sure they are Sino-smart:

Journalism: https://chinarising.puntopress.com/blog-2/

Books: http://chinarising.puntopress.com/2017/05/19/the-china-trilogy/ and

https://chinarising.puntopress.com/2018/06/18/praise-for-the-china-trilogy-the-votes-are-in-it-r-o-c-k-s-what-are-you-waiting-for/

Website: www.chinarising.puntopress.com

Twitter: https://twitter.com/44_Days

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/44DaysPublishing

VK: https://vk.com/chinarisingradiosinoland

About me: https://chinarising.puntopress.com/about-the-author/

Sixteen years with the people on the streets of China, Jeff

Downloadable SoundCloud podcast (also at the bottom of this page), YouTube video, as well as being syndicated on iTunes, Stitcher Radio, RUvid and Ivoox (links below),

I am truly honored to have Amir Khan on the show today.

I read Amir’s latest book, “Comedies of Nihilism: The Representation of Tragedy Onscreen”, which will be the focus of our discussion today.

I highly recommend to all China Rising Radio Sinoland fans to read Amir’s very engaging and informative book about all-things movies. For film hounds, it’s a must! It is available in ebook and print format below. If you don’t have the money, ask your local library or school to order it. They have annual book buying budgets and LOVE it when readers make requests.

After listening to our discussion and hopefully reading his book, like me, you will likely go see movies in the future with new eyes and a fresh perspective on cinema, and what it all means to modern culture. We discuss how it all relates to the headlines, the “Woke” movement, identity politics, imperialism, the deep state and more.

Contact: am**********@dl**.cn

Website: https://dlmu.academia.edu/AmirKhan

Book can be purchased here: https://www.palgrave.com/us/book/9783319598932

Transcript

Jeff Brown – Good evening. This is Jeff J. Brown China Rising Radio Sinoland from Chiang Mai Thailand, and I am super pleased to have on the show today Mr. Amir Khan. How are you doing, Amir?

Amir Khan – I’m doing very well Jeff.

Jeff Brown – Hey, listen, I think you’re in Dalian, China, right now, right?

Amir Khan – Yes, that’s correct.

Jeff – Up by Korea and Japan, Yes, a long way from Chiang Mai.

Hey, listen, the reason we’re here together is that I read Amir’s. Well, I think he’s written three books, but are two or three books. But I’ve read his book about cinema, and I’m super happy to have him on the show. His book is called Comedies of Nihilism. The Representation of Tragedy on Screen. So that will be the focus of our discussion today. I highly recommend to all China Rising Radio Silent fans to read Amir’s very engaging and informative book about all things movies for film hounds. It’s a must.

It is available in e–book and print format below. This will be on the article page on China Rising Radio Sinoland. If you don’t have the money, ask your local library or school to order it. They have an annual budget to buy books and love it when readers make requests. I have and I will include Amir’s email if you’d like to contact him later. He has a website page where he is teaching at the Italian Maritime University and I have the link to buy the book.

So welcome to the show, Amir.

Amir – I’m very happy to be on China Rising Radio Sinoland, truly.

Jeff – Please tell us a little bit about yourself, your past and present, and your arc of awareness about the connection between movies and global imperialism.

Amir – Ok, the first thing I’ll mention is that I’m Canadian, I’m working in China, as you mentioned, Dalian Maritime University, but I finished a Ph.D. at the University of Ottawa in 2013. And I wrote my first book was my dissertation, which was on a Shakespearean tragedy. And my second book is a book of film criticism, Comedies of Nihilism, which we’ll be discussing today.

And basically, one of the things that got me thinking about cinema after writing about the Shakespearean tragedy was just wondering if anything at all like tragedy is actually can be rendered in a kind of a similar way on the cinema screen. So I was thinking about that question a lot.

And I wrote my second book sort of at the same time as I wrote my dissertation on it’s kind of I was on the side. Yeah. So both of those books came out or were published relatively close together.

But my central thesis in the book is that movies are about nihilism and are about meaninglessness. The most serious movies. I mean, the most serious movies that we may be consumed in and take them to just maybe kind of be like popular, maybe not giving them much thought, but serious thought. But I think that there is a sort of a message, a very serious message that is sort of rendered very well in the movies that I talk about.

But it is this idea of a sort of cultural meaninglessness or nihilism. And you could call it a sort of type of decadence. They’re sort of critiquing Western decadence. Now, there are all sorts of ways that decadence appears in these movies. And I’ll say at the outset that the book, it’s a book of esthetic criticism. So it’s a close reading of the films themselves.

So I’m talking about what’s going on internal to the films. And I don’t spend a whole lot of time discussing, see the social, social, political, economic realities surrounding these films that maybe have led to these feelings of nihilism and cultural decadence.

But of course, those things also matter. One thing I’ll say just, in terms of the connection between movies and global imperialism, is that one thing to keep in mind?

You know, sort of one of the outer reasons why movies really can’t get anything across that are very meaningful anymore? One reason, I think is because movies are so capital intensive and because of capital intensive.

It means that there’s a lot of risk in making a movie and when there’s a lot of risk in making a movie, people are not as willing to tell interesting stories or to tell anything that could maybe rock the boat. So that is one reason I think that these movies, these movies are sort of aware of being hemmed in that way and are sort of responding to that.

And like I say, they’re not responding to it by, say, critiquing society or critiquing the social or political or economic realities that movies find themselves in. But I think they’re critiquing something that. We feel when we watch movies nowadays, which is we feel like they don’t have anything to say, that they can say with any kind of sincerity and get that across in any sort of meaningful way.

Jeff – Yeah and that’s why we have Spider-Man 7 and in a way, Superman 12.

Amir – Like in that article that you sent me, a ride like that’s what Martin Scorsese was saying like all of those movies have been vetted and audience-tested over and over again and only when they work or they are released.

Right. But that sort of takes away from any kind of I mean, we know what we’re getting in advance kind of thing.

Jeff – Yeah. Yeah, exactly.

Hey, listen, in Comedies of Nihilism, you review, analyze and critique eight very diverse movies. And you frequently cite Stanley Cavell. And I’ll spell his family name for the fans out there its CAVELL. And I have read, Gene Siskel and Roger Ebert and Leonard Maltin and a little bit of Pauline Kael back in her heyday but before we get to the movies, why do you think Carvelle is so important among movie critics?

Amir – Stanley Cavell, the latest individual who passed away recently in 2018, I think, I mean, he’s a major influence in all of my thinking and all of my writing, even my writing on Shakespeare.

But I think the reason it’s important to acknowledge, at least for me to acknowledge Stanley Cavell, is he was sort of a pioneer in writing about a film very seriously.

Nowadays, I mean, you look around and you see departments of film studies at universities everywhere and departments of cinema studies. It’s very common for people to get, an army or a Ph.D., by studying film and even like popular culture. It’s sort of taken for granted. It’s very much sort of the academic norm or academic fad right now to write about these things. Anything?

Yeah, anything you see, like on TV, like a Netflix series or even like YouTube, show, or anything like that. I mean, there’s a good chance that somebody out there in the academy has written about it, on a serious monograph or article study about all of that kind of stuff.

But Stanley Cavell, again, was writing about the film before all of this sort of became popular, sort of a pioneer in that regard. So he wrote two important books. Yeah, he wrote two very important books. And the first is The World View, published in 1971. And the second, my favorite Pursuit of Happiness in 1981.

And he did it from the institutional point of philosophy. So philosophy is always a bit reticent, I mean, they do talk a lot about the esthetics and why we feel the things that we feel. But, when you’re talking about esthetics and philosophers probably feel that you’re much better off looking at a philosophical treatise by, contour Plato than you are to read a Shakespearean play. So there is this tension between philosophy and literature already reading any works of sort of imagination there’s always suspect, I think, in philosophy departments a little bit anyhow.

But Stanley Cavell sort of went on further and you started talking about movies, you know, at a time when movies, weren’t considered necessarily high art by any means. Right. And not only did he talk about the movies, but he also didn’t talk about some, French foreign films or some avant-garde theater that’s very obscure. Anything in pursuit of happiness. Anyway, you talked about early Hollywood talkies. Yeah. Which were considered. Yeah.

By the late 1930s or early 1940s. And, those were essentially dismissed as sort of romantic pop wailers where there’s a happy ending. And, the Philadelphia Story is probably like, the landmark kind of there are the most. Yeah. And the most notable one that he talks about.

And nobody at that time would ever consider giving any type of academic seriousness or academic scrutiny to a film like the Philadelphia Story and certainly not philosophical scrutiny.

You know, putting a philosopher like Kant next to a discussion of the Philadelphia Story was just something you didn’t do. So Stanley was very unique in that way. And he sort of achieved that. And he’s managed to garner I mean, I wouldn’t say, the mainstream of philosophy is sort of been taken with his work. But he does have, I guess you could say, sort of a cult following. And Stenico is respected within, philosophical circles and stuff like that.

But he did something where he thought movies, which were taken to be, what you might call a low type of art. He thought there was something very philosophically significant and important happening in those films. And in the same way, in my book, these seven comedies, you could almost dismiss them as a type of stoner comedy.

It’s just teenage kids watch on the weekend when they’re, doing certain things. Yeah, but I think that if they do have that kind of appeal. But I also think that there something very serious going on in these films. They are hilarious. They are ridiculous at times, but they’re also very violent. So Stanley Cavell is a pioneer in allowing me to do the kind of work that I did.

Jeff – OK, cool. And that’s what let’s start with movie -1. One up in the air and your review of the movie, Up in the Air, you talk about a manufactured word quite a bit Glocal. And I loved it because it’s cool. It’s what English teachers call a portmanteau, which is it’s I mean, it’s a French word for a hanger to hang clothes and that’s squishing two words together to make a new one like brunch, for breakfast and lunch.

So Glocal is like, global and local. What does it mean to you and reflect on the word glocal when reflecting about today’s mainstream headlines?

Amir – So Glocal is the word uttered by the Natalie Keener character, played by Anna Kendrick in Up in the Air, and she’s making kind of a business presentation at the time again just a brief primer of the movie Up in the Air. So basically, George Clooney, who plays Ryan Bingham in an agenda to play as Natalie Keener, both of them work for a firm, and the job of the firm is to fire people.

So basically, companies will hire like these characters will hire them to do their dirty work, like, let’s say instead of the H.R. department or something. They will hire people who work for this firm that George Clooney and the candidate that they work for.

And then they will go and they will offer a severance package or whatever and let the person know they’ve been let go because the company is too afraid to do it themselves. So that’s what’s going on Ryan Bingham, George Clooney does it the old way where he meets people face to face and shakes their hands or whatever before Delta, you’re fired. Donald Trump or something. So he does it that way.

And Anna Kendrick, the character, Natalie Keener, comes in and she wants to change everything she wants to now by video screen. Yeah. And the logic that she uses, which is making kind of a pitch to her boss and she’s saying we have to make the global-local so we have something that works. Yeah. We have to take something that works kind of like, in the name of efficiency or the name of profit. It’s right on a sort of on a grander scale that allows us to do these things more efficiently and more but in a more profitable way.

But we have to make it feel like we’re standing in person like we’re standing next to in person. So we have to make the global-local. So that I mean, your question about, today’s headlines, I mean, I think that and I say this is the film that something like that betrays the direction of knowledge or a sort of the direction of the types of business strategies that are in place that are going on all over the world, you know, in whatever industries maybe, even in the film industry, certainly in this industry that they’re talking about in this movie, and that they’re not seeking to take something local. Right. And make it global. So the word is not global.

OK, because first of all, that word doesn’t sound as good. Glocal just sounds better. But the idea that. You don’t businesses are not interested in taking things that are happening in the grassroots and sort of blowing them up, that’s not the direction I think that sort of late capitalism. The times that we find ourselves in now, we have we’re more interested in sort of imposing. Yeah from something global we want that to be local.

And how that might play out, let’s say, in movies or cinema or terms of, an idea of nihilism is that when stories or representations or business strategies come from elsewhere and are imposed upon people, they don’t speak to people’s actual experiences on the ground. And if they don’t speak to people’s actual experiences on the ground stories, for example, then the stories themselves become kind of meaningless. And that type of logic leads to a type of nihilism. Yeah, already knowing the answer to that, this kind of thing.

Jeff – Ok, cool. In the same critique for the movie Up in the Air, you talk about Canada being a cultural mirror for the rest of the world. Why?

Amir – Ok, that’s a very good question, and I said.

Jeff – you are Canadian and since you are Canadian…

Amir – Sure and one of the most outrageous things that I attempt to do in the book is I have this sort of double-pronged thesis. I want to equate the failed esthetic promise of movies. You know, movies don’t have anything to go. You don’t have anything left to say, particularly under the constraints that they currently find themselves in. They can’t say anything meaningful. I want to equate that feeling with the failed national politics of Canada.

Yeah, and that’s kind of what I call it like a subplot and so now how does that work out? What I think is in terms of sovereignty. The politics of Canada in terms of building a sense of sovereignty or a nation as a sovereign nation has truly failed. And why is that? There are two main reasons. First of all, by its geography alone and by its language alone, we’re right, of course, next to the United States and we speak the same language as the United States.

So the cultural onslaught that we get from this English speaking bohemian to the cell is so powerful and so daunting that for us to even have attempted as a nation to carve out a sense of sovereignty for ourselves was sort of, it was never possible, to begin with.

Jeff – It was almost like a pipe dream.

Amir – Kind of. Yeah, exactly. Totally. And this wasn’t this isn’t something that I’m just realizing now.

This is something that was written about very seriously by, I say a host of, I call him sort of Canadian philosophers who rose to prominence in the nineteen 50s and 60s and 70s. They understood this problem very well, very acutely, and they were theorizing about it.

And what I felt was when I was reading their work, and what they were saying is sort of the same feeling that I have when I watch certain movies, these seven movies, these companies of nihilism because they’re kind of saying the same thing differently. They’re just saying that we are at the end of an expressive medium of cinema that is exhausted. And what these theorists were saying is kind of like we are at the end of this cultural experiment that we tried, which is called Canada.

Jeff – Yeah.

Amir – And I’m trying to make the case that those feelings are the same.

And one book that I talk about a lot that is the father of Canadian philosophical pessimism, you could say is George Grant, who wrote a book in 1965. He called it a Lament for a Nation that was in 1965.

Yeah and in that book, he declared, Canada is no longer a sovereign nation. And really, and yeah that far back and really how you have to think about it is that when you are on the receiving end of the cultural shockwaves, if you’re not interested in the idea of sovereignty, if you’re not interested in that question, I think Canadians today are just largely uninterested in even asking this question.

They just take it for granted. They have a flag and they have a currency and they have an anthem and they think, OK, so we’re a nation, but they don’t ask themselves what this possibly means and whether or not by the fact, OK, first of all, the geographic location, by that fact, that’s one. Number two, we speak the same language as the Americans.

So and if we speak the same language, it’s very possible. And it’s very like we think language. And if we think in the same language, why is it so hard to believe that we think the same?

Because of all of our media in Canada and all of our, the things that we consume in the English language, I mean, the bulk of them just we are bombarded, of course, by the cultural onslaught emanating from the United States and a country like Mexico, let’s say, could at least hope.

And I’m not saying that they’ve been successful in doing this in any way. Maybe they have, maybe not. But at least in the language, in the Spanish language, you could at least hope to carve out some sort of sovereignty for yourself or your country, but lacking any type of bulwark in that sense, speaking, carrying on in English, and just taking your identity for granted in a way means that you have no identity.

And I do think that that’s true. And so I’m just going to your question about a mirror for the rest of the world. George Grant even says this. He says much greater traditions are going to go than minor most loyal traditions than just minor, loyalists. We were loyal to the British crown. when the Americans declare independence, we’re a minor loyalist tradition.

There are much greater traditions out there that the cultural onslaught of American cultural hegemony is going to just boil over. And it’s happening. It’s happening. And I think anywhere that English goes, you have to deal with this import, this cultural import, I mean, the language of force and the English speaking language is a force. And if other nations were sort of interested maybe in reading about Canada’s effacement and that in a sense, Canada could be a cultural mirror in the way that you speak of.

Jeff – Yeah, that’s well said. I also think I loved your comment that the computer does not impose on the way it should be used. In other words, it’s up to the user to make it useful or diabolical. Are you a Luddite, a tech slave, or somewhere in between?

Amir – That’s a good question. So this is also a phrasing by George Grant. He’s talking about technology. And again, that was in my discussion of Up in the Air. And it goes to that idea of the computer does not impose on us the way that it should be used. That sounds factually true. No technology tells us how to use it. Technology is neutral and human beings can decide whether to use it or not to use it. And we want to believe that that’s true.

But I don’t think that is true in the movie. And up in the air, they have a choice. We can fire people by meeting them in person and spending a lot of money doing it that way for humanistic reasons. Or we can do it via video screen and maximize profits like we know the answer. Do you see what I mean? Technology is always the answer for us, you know. Well, the technology and logic of late capitalism and stuff like that. So, I mean, I would say I’m a Marxist and I’m suspicious of technology in the way that Marx was suspicious of technology and what he calls technology fetishism.

If we can do something by technology, it’s making a humanistic stance or taking a humanistic sort of opposition to like, oh, but we shouldn’t do it that way because it’s not right. Or and it’s almost ridiculous in and of itself. If we have the technological capability to do it, we’re just going to do it. I mean, it’s just going to happen. And in the film, George Clooney, his boss, played by Jason Bateman, Craig Gregory, kind of says he does cocaine.

IBM has been doing this for years. Never heard of them. Well, there you have Coke and IBM are doing it. I mean, what’s the chance for Ryan Bingham and the movie of stopping this logic? Right. If we can’t do it, we will do it. So in a way, you know, I’m a Luddite in the sense that, yes, I’m suspicious, but I’m also a tech slave. I know that there’s no way you can stop it if we can do it. It’s just happened that technology imposes on logic. Yeah. And I think that’s very dangerous.

Jeff – Another great comment you made is this one I thought was quite profound. You made the statement that the ascent of the novel would not have been possible without the rise of the nation-state. Please tell us about that.

Amir – That is Ian White’s thesis. So I was talking about the book by Ian watt he wrote a book in 1957 called The Rise of the Novel, and he’s talking about the 18th-century novel and definitely, the novel was very useful too, a political project of nation-building was also very politically useful to a project of building markets. So the novel was kind of like the perfect art form for the rise of the nation-state. I mean, this is kind of what you want is saying novels are consumed in private.

You create this private sphere that never existed before. A person in his reading room reading a novel consumes the novel alone. So a lot of the rhetoric of private property and stuff stress this idea of the individual, so a novel is a form.

Yeah, a novel is an art form, sort of could be exploited that I mean, it created it’s not like going to the theater, which is kind of a communal experience. Right. Into the esthetic issues that you have in private, in a way. But the novel also instructs the individual on how he or she ought to live or perceive or take note of what’s happening in the life of his or her nation.

Yeah, usually the main protagonist is involved in all kinds of ways things that are going on in the country or things that are of national importance or whatever. So the novel helps us understand ourselves, as private citizens within a public administrative structure known as a nation. So the rise of the novel. Yeah, it’s almost the perfect art form with the rise of the nation-state. And I say inversely, the movies are the opposite, that movies are concomitant with the decline of the nation-state or the decline of the West. What movies are Spenglerian (after Oswald Spengler)?

Yeah, so. And, I can just kind of go on a little bit about that, the writing novels, in a sense, Jon Ralston Saul makes this point and I say to my book, novels or participatory words are more participatory.

They require an act of imagination. You have to imagine yourself in among the community that you live in. Yeah. Because you’re only given the words you’re not you’re free to imagine how those words mean to you much, but you have much more freedom than you do when you’re given an image because an image, all of that is sort of dictated to you and imposed on you consume cinema and a much more passive way.

And I would say, kind of inversely to you in what he says, that the rise of cinema for the nation to be represented in the cinema, the passion to the imagination, that the nation has to be imaginatively sorted out already. There has to be a stable sort of idea of what the nation is. It gets represented on screen and we just sort of passively consume it.

So that means that in a way, nationalism or nation already has sort of reached its height. In a way, there’s over the hill and once it’s reached that stage, then cinema is maybe a bit more natural fit as a democratic art form.

Jeff – Fascinating movie – 2, Tropic Thunder, and this is the one movie I’m embarrassed to say, but this is the one movie you critique that I saw, and that was a long time ago. I had forgotten that it was a movie being shot within a movie until I read your chapter on Tropic Thunder. And I remember had Ben Stiller and I remember it as kind of a grotesque spoof on war and racism, set in Vietnam, maybe even trying to desensitize us to them and to, war and racism.

So just since I saw the movie and it kind of gave me a different perspective in reading it. Just tell us what Tropic Thunder meant to you and why you included it in the book.

Amir – Ok, Tropic Thunder is in many ways, I mean, it’s almost like a quintessential or sort of a tell in the genre that I’m talking about, because, as you said, the spoofer, the spoofer, it seems just endless.

Ben Stiller almost seems to be spoofing in a very aggressive fashion.

I mean, just anything there is nothing that is sort of sacred in this movie, And the sort of the shibboleths of identity politics are all spoofed very early on, right in the beginning whether it’s discussions about intellectual disability or discussions about obesity or discussions about race relations and hip hop culture or discussions about homosexuality, I mean, all of it is just kind of make fun of spoof, all of the things that we think are very important in our lives and sort of all of our sacred cows.

So that’s great now. And a lot of ways that Tropic Thunder, again, just looks like it’s spoofing for the sake of spoofing. And the levels of irony, I think are very intelligent. As you said, there’s a movie shot within the movie. And what we are aware that we are watching a movie about the making of a movie, the movie, and the movie.

It’s also called Tropic Thunder, watching a movie about the making of the movie called Tropic Thunder. And the movie in the movie is based on a memoir also called Tropic Thunder of a Vietnam War Hero. And in the movie, that memoir turns out to be fake.

Yeah. So there are all kinds of the layer of irony. I mean, there’s three or four right there and it almost just seems ridiculous. It just seems like, OK, where are we going with any of this? And I certainly don’t say that the film is ridiculous, even though it seems that way prima facie. But definitely, I think it is a very intelligent movie. And like you say, Ben Stiller is a star and he’s also the director.

And what do I think that he’s trying to say in this film? Definitely what I think he’s doing is he’s mainline of critique. The mainline of spoofy that he’s talking about are the representations of the American war experience in Vietnam. That is first and foremost, I think, what that movie is talking about. I mean, there was a very famous Vietnam War movie called Rolling Thunder. This one’s called Tropic Thunder. And the movies by Storm.

Yeah, movies by Oliver Stone, born on the Fourth of July and Deerhunter, Platoon, Yeah. Deer Hunter, of course, another one. So there is a whole genre of movies that attempted to do something. And it’s really interesting if you think about probably what they were attempting to do, they were trying to sort of deal with the trauma of the American war experience in Vietnam.

And still to this day. Right. It’s still not clear to Americans or what we were doing in Vietnam, whether we were we or whether they were good in their intentions.

And I think even Bill Clinton even said our intentions were originally good. I mean, we just got caught up in all of these things that just got taken went too far. So I don’t even know if America itself is clear on whether or not it should have been there or shouldn’t have been there or was there with good intentions and just kind of messed things up tactically rather than morally.

Now, one thing that all of these movies do and you know, again, Jon Ralston Saul has a great critique of Platoon, which I think I footnote in my book.

In those movies, there’s an interesting, you know, the American war experience in Vietnam becomes a morality play like why the Vietnamese were fighting or what their political agenda was or why they felt the need to go to war with America themselves or to fight back. I mean, they were attacked. This was an aggressive nation invading their country.

But why never are these movies ever interested? Very much on the Vietnamese store where they’re coming from with their political beliefs. So what happens is yesterday was a bad thing that we were in Vietnam. And the Vietnamese people are sometimes they’re represented, but they’re only as props just to kind of have this morality play going on where it’s about America and it’s about the individual consciousness. And America is trying to exorcise its demons. Even the finest so-called films like Platoon is very much like this.

It’s a total denial of the other Vietnam experience in this horrible act of, you know.

Jeff – Killing millions.

Amir – Sure.

So and here’s the thing, right. Like C. Wright Mills wrote this book in 1957 called The Power Elite, and President Eisenhower warned the nation about this military-industrial complex.

And then suddenly America went to the movies after the power elite and the military-industrial complex sort wreaked havoc on Vietnam, America went to the movies to attempt to deal with this trauma.

And there was all this moral hand-wringing and there was supposed to be this sort of catharsis or sort of the change in the American experience or psyche or whatever. And really what they were trying to do is they’re trying to curb, in a way, the American war machine., if we’re repentant, then at least we should stop doing the things that we did like Vietnam. But if you look at the 21st century, there’s already been four Vietnam, at least, Afghanistan, Libya, Iraq, Syria, and there’s more Sudan or Somalia.

And you can’t, I mean, they’re all over the place. So what this movie Tropic Thunder is expressing, I think the frustration that exists expressed and why it’s spoofing, such an aggressive manner is because we are that generation that Ben Stiller’s generation went to the movie and was made to go through all this moral conflict, made to go through all of this hand-wringing and, oh, my God, it’s such a terrible thing we did.

And it has not changed anything it has to see in the American experience or how the American war machine operates. If you look at something like, OK, so now like the military-industrial complex, it’s become common parlance nowadays. It’s like the deep state and the deep state is much more prevalent in our lives.

Then we took the military-industrial complex to be or what we took the power elite to be. I mean, and they’re much more entrenched and there’s nothing we can do about it. There’s no way we can change the life of a nation the way that it wanted to. And that, I think, is a vision of nihilism. And I think that’s what Tropic Thunder is trying to get across.

Jeff – Well, maybe I want to watch that movie. Maybe after I retire, I’ll go back and watch all these movies, because after reading your book, they came alive for me, even though this is the only one I saw. But, I really should go back and watch when I have the time.

Movie – 3. JCVD and that stand for Jean-Claude Van Damme and when my wife and I owned a CD and DVD store in France in the late 1990s, of course, we were in France. And, Jean-Claude Van Damme, I’m pretty sure he was from Belgium, isn’t he?

Amir – Correct. Yes, his nickname was “The Muscles from Brussels”.

Jeff – Yeah. I always took Jean-Claude Van Damme as a bit of a joke, we would get his DVDs and stuff, in the store like a grade B actor. Yet Rotten Tomatoes gives his movie that you reviewed JCVD the initials of his name, very high marks. I mean there’s like 85-86% on Rotten Tomatoes, which is like sky-high here. Here are some notes I took while reading your chapter on the book you wrote, We Live Violence by Proxy through watching films.

The function of civil society is that action movies purge us of our violent proclivities as the case has been made rather than exacerbate them. So do you agree or disagree? Why or why not?

Amir – Well, I think yet the case has been made. I mean, I think most famously, I can probably say by Aristotle, he was responding to Plato and Socrates, you know, famously banned the poet from the republic. So we don’t need tragedies in the republic, it’s kind of interesting, esthetically pleasing, but we don’t need that stuff, and but in the ideal city and they also left the door open. If anybody can think of a reason why we should let the poet back in, you’re free to comment.

And a generation or so later, Aristotle came along and he just said, no, no, no, the trade unions are good and tragedy is good because it allows us to achieve this catharsis or purging of pity and terror.

So it’s kind of these psychological uses and that’s good for the soul. And that kind of argument has been made right about violence in movies, right? Oh, yeah. When we go to the movies and we see all these we see all this violence and you see all the sex, it gets it out of our system. And it’s it does sort of a kind of ethical work. And it’s good for the soul. Yeah. Oh, it’s true. Yeah. People argue. Yeah.

So we can we need to keep it in there or whatever. And also whether I agree with that or not, I don’t think I agree with that. But in terms of why there’s so much violence and so much, sex and pornography, particularly in the West, I mean, I just think that that is a symptom rather than a cause of nihilism. And we know that nothing very significant to say otherwise. So sometimes you try to hide that or mask it through a sort of exhibitionism.

And that’s why you see kind of these. Yeah, that’s why Western movies in particular always have a tendency to stylized violence and sex, but probably, no other art form or no other industry is interested in doing well.

Jeff – They’re talking about that right now with the movie The Joker. that well, is he? They’re using the exact they’re talking about the same thing. Is he causing people to be violent or is he right? is he helping us, appease or reduce our desire, etc.

All right, another one, you said women are held silent throughout the movie, but as it progresses, the men are silenced, which says that the further pacification or feminization of men in American cinema has now clipped its action stars. And of course, Von Doom is an action star who is no longer able to speak or act. So men are forced to love and be silent as less expressing female subjectivity than survival. The systematic loss of subjectivities is tragic. That’s deep. Tell us what you think.

Amir – Sure, I wrote that I was trying to address because in the movie JCVD, there is no significant female role and I wanted to address why I thought that was the case a little bit. Now, I’ll just sort of say the in terms of the pacification of the American male, you know, that’s something unique, I think, to American cinema, as the American leading male.

Right. I mean, if you just think of, like the Cary Grant or the Spencer Tracy’s are not they need to be there to get to the happy ending. That we want him as a romantic leading male in American cinema. You cannot be sort of aggressive in a way. You have to be feminized or you have to be pacified in a way.

So Stanley, come out, puts it like the leading the person who is the candidate may be to be like leading American actor protagonist has to be willing to be struck down. I mean, in a way, you have to be you have to show that you’re not so proud that you can kind of handle, you know, kind of humiliation of sorts and still retain your dignity and still be a man that way.

That’s true, right? I think that’s true. Like, definitely in the romantic comedy tradition, it’s not like a knight in shining armor comes and sweeps the woman off her feet.

And that’s it in a way, no, you have to kind of know-how to seduce a woman. You have to talk to a woman. You have to be gentle. You have to be a gentleman. And so the leading male in American cinema has always been sort of pacified. And you could think of the genre of the hard action movies which came to prominence, you know, in the late 1980s and early 1990s and even maybe Westerns in a way that’s sort of pushback to this type of trend that was going on in that in sort of the mainstream of American cinema, that males need to be sort of strong, silent, not speak so much and just get in there and not by and get the woman not by, sweet her, but just by kicking ass and getting things done, you know?

Jeff – Yeah, it was yeah.

Amir – There was this kind of pushback, I think, and there was a lot of appeal to these kinds of hard action movie stars, especially, about this Jeff. I grew up in the 80s and you know, Stallone, Schwarzenegger.

Jeff – Oh, yeah. And also Clint Eastwood and Dirty Harry.

Amir – Yeah. That was not a genre too but then also Steven Seagal and Jean-Claude Van Damme, I think for me with the Big Four and whenever they had a new movie coming out and, I just remember I was a kid and I was so excited to go see the new action movie. And when I claim is like there’s another genre of movies, another genre of movies that he gets to the end, he jumps up and down.

That is kind of explored very intelligently, I think, in that film. Jean-Claude Van Damme, in that movie, plays himself, but he has everyday kind of problems, just like the rest of us.

He’s not a custody hearing. He’s trying to transfer money to the states so that his lawyer has enough money to defend him in his custody hearing and he can’t get anything done, not in the manner of what you think of somebody like Jean-Claude Van Damme could do it.

Yeah, action movies. It’s just kind of ordinary, everyday stuff and jumps up and down. That’s true. He was taken to be a joke, especially in Europe, because he did a lot of quasi philosophizing and I think like on TV series, but not in any of his hard action movies.

Precisely. But he’s always trying to kind of explain and make sense of his life. And I think, Jean-Claude Van Damme, in the genre of movies that he finds himself in, he finds himself silenced by the very genre movie he started. I can’t explain my life by using, the hard action formulas that worked for me and my movies. And I’m trying to kind of philosophize them and talk about them. But I also still can’t make sense of them in any way and in a way, as that movie progresses, he is silenced.

He’s silenced by the work that he’s done previously and he doesn’t really know how to speak about or even if he’s found any new-found knowledge or again, had any sort of cathartic experience because of his life, because of his career. And it’s very sad and tragic. And he’s presented himself playing himself in a very vulnerable way. And at the end of the movie, we shouldn’t give away spoilers here.

But he’s arrested for charges of extortion. He’s heading off to jail. And there’s a person who sticks a microphone in his face like a reporter and says, no, I asked him to comment or whatever. And Jean-Claude Van Damme just knows that things are kind of a telling moment in the film. Just kind of brushes are off and refuses to answer. He refuses to speak.

It’s almost like, yeah, at the end of the film, he’s kind of refused to try and explain his life in any way to himself or to make. That’s because the expressive possibilities are lost. I think that that’s kind of the realization that he comes to you and I make the case that he has kind of silence in the way that we normally think the women are silenced. And, you know, I kind of think another great reading.

I kind of say that I compare his tale to the King Lear tale and Cordelia, who says maybe I should just love and be silent. But of course, Cordelia is not silent. She speaks up. And then the whole tragedy of Lear unfolds. And the lesson maybe would be that, OK, we didn’t just keep silent or not speak out. That’s what I think it should be or anything like that. But I think that in it similarly, he also learns like, OK, I just I’m it’s too treacherous for me to speak out.

Jeff – Especially today with all of the freaking, identity politics. And what are your deal with the Awakening movement and all that stuff? Just like they say comedians can’t even do comedy anymore.

All right, movie – 4. Winnebago Man and you wrote to the documentary, Watching a man being degraded or degrading himself is only enjoyable when we don’t know that person. Otherwise, it’s spoiled. Please explain that.

Amir – Oh, yes, that is a quotation in the film by Charlie Sotelo and Cinco Barnes, who are a couple of you know film buffs and I’ll just give a bit of a primer here about this movie Winnebago Man. So Winnebago Man is a documentary and documents, Ben Steinhauer. He’s the director. He goes in search of the Winnebago man. And the Winnebago man is a person who came to some notoriety.

He was original, I think sometime in the 80s, used the promotional lead or he appeared in these promotional videos for Winnebago Industries, advertising for the Itasca Sunflower RV. And at one, there as he is shooting, he’s this polished urbane sort of salesperson. And then suddenly, like I was a fly, would come into the room or be too hot or something.

He would just start swearing and just very comically very funny. You see kind of this polished, urbane human being that you just see him losing his temper. Anyhow, unfortunately, there were some people on set working with him who distributed the outtakes via VHS tape recorder, and they got spread around somehow. And then they and anyway, it was he became too much of a liability for Winnebago Industries. So they let him go.

They fired him. And then with the rise of the Internet and with the rise of YouTube, those same clips were disseminated electronically. And Jack Rebney the Winnebago man who’s always losing his temper and became a sort of an Internet celebrity.

But the idea was, and this is showcasing the movies that he, after the humiliation of all of that, went into hiding. And Ben Stein, back to the film’s director, goes in search of him. And he’s talking to some people in the lead up to, you know, finding Winnebago man. And he talks to Charlie Sotelo and Cinco Barnes and they say, no, no, no, why are you going in? They’re not talking to Ben Stein. They’re saying, I don’t want to know the person who I watch these degrading videos. It’s no fun. It’s only fun to watch these videos of somebody kind of making.

Oh, yeah, it’s only fun if I don’t know the person. So, I mean, in that way, sort of saying it’s a type of schadenfreude. Right. I’m only enjoying these videos or only watch the videos because I’m watching a person who isn’t me getting humiliated. And that’s great. But the interesting thing is that Ben Steinbauer was a film director, doesn’t do it for reasons of schadenfreude, he loves those videos.

He watches them, he considers them, but he’s going, I think, in search of Jack Rebney Winnebago to discover why he’s so fast. And he presented this idea and his basic idea, OK, maybe it’s only hoddy for me, but I don’t think it is.

And the movie is wonderful because it documents his discovery and his journey of the real reasons why he’s been so fascinated with this individual. It doesn’t very well. Interestingly, it’s very moving once you get to sort of the film’s climax.

Jeff – Also in Winnebago man, you talk about oppositional cinema and that the best ones don’t even know that they are oppositional cinema until maybe after the movie comes out or even years later when people discover they’re. So tell us what oppositional cinema is.

Amir – Oppositional cinema so is a term that was coined by Robin Wood, a great film critic, is Canadian. He taught at York University.

So he talks about oppositional cinema. And the interesting thing is when I was reading his discussion about it is he says he has some favorites that he calls oppositional cinema. Real Problem by Howard Hawks was probably the most famous example of his. He thinks that’s a great piece of oppositional cinema.

But what’s more interesting to me is what he takes oppositional cinema to be. Exactly. It’s like you said, it’s the ones that they don’t even know that they’re oppositional. So there’s no intent at the outset. The director now says, OK, I’m going to show you my critique power. I’m going to write or I would like a social documentary that exposes this or that. So it’s not like we’re watching a Michael Moore film is not oppositional cinema in the way that Robin wrote is talking about.

He’s talking about the free-flowing creativity that you need and the only self-consciousness that you need to tell a story honestly and genuinely. And that if you tell a story honestly and genuinely, there will automatically be oppositional elements within it that if they’re allowed to breathe but simply by being represented, they will get out there and do the work that they’re supposed to do.

But if you can achieve as an artist its stance, sort of candidness or, you know, what Matthew Arnold might call interest, only then can you sort of mind a story or the art that you are trying to present to the world. Only then can its oppositional content shine through. So, yeah, you can’t be aware beforehand.

Being aware of the end goal of the sort of creating oppositional cinema is a sign of documents or selfishness? Well, according to John Grierson, I highlighted that in my book as well.

But so you have to have your guard down in a way because if you have your guard down, you let things sort of coming through to the floor. And I think that this film, this documentary film, Ben Stein, and it’s documented very well, he doesn’t even know why the hell he’s going out in search of the Winnebago. And then when he finds Jack Rebney, he doesn’t even know what to ask him or what to ask him to do, or he’s got a camera on him and he’s got to do something.

And he said what should be doing flirts with the idea of maybe we’ll set up a podcast, Jack, you can just start ranting and people will listen to that. But he has no real idea why he’s doing what he’s doing. And like I said, the movie does work towards a very moving climax.

And, what happens is, I mean, I claim that Jack Rebney meets for the first time, sort of faces the people, face the same people who have been consuming these videos online. And I have found footage, film festivals. And these people who have been consuming jack revenue anonymously for all this time now are faced with the real human being and both of them in each other in a very moving way.

Now, both of them recognize in each other how much each of them speaks to each other because neither of them is very interested in engaging with direct oppositional politics. Quite frankly, they’re not. And I say this in the book, why would anybody want to do that? If the language of identity politics or the language of, you know, there is a politics, Republican-Democrat or what have you. All it does is provide the language of discord, right.

It doesn’t provide grounds for treatment or grounds of agreement of any kind. It only creates people who are bickering with each other. And what the Winnebago man and the Winnebago man’s fans are kinds of doing is they’re hiding from over that. They’re hiding the type of anonymity.

But that type of anonymity can never be known in public. But Ben Stein values great achievement is he found this anonymous sort of Synergy this is anonymity between Jack Rebney and his family, who only exist outside of any actual direct video cameras filming them. And they sort of found each other in anonymity.

And what they’re trying to do essentially is they’re trying to kind of build in a way I say this in the book, the reason that they consume all of these Jack Rebney videos is they’re trying to come up, first of all, with a sense of community, because if you have a sense of community, then the political world can follow.

But if you don’t have that sense of community, you just go and you arguing that issue or whatever. I mean, it’s just never going to go anywhere. And I think that’s a very profound political statement that Ben Stein the director, never meant to document in the first place, and he managed to achieve that. And I think that that is very oppositional. That is that is very political. So that’s what I tried to say.

Jeff – Talk about a fascinating movie – 5. The Trotsky, you use the comments on a play. The actor is the projector as in the film projector. On the movie screen, the subject is projected. Why the difference and why does it matter between movies and plays?

Amir – That is very important, I would say, ontological difference, especially when talking about tragedy and Stanley Cavell, who kind of made that sort of quip about in the playhouse, how the actor got a projector. And that is true.

So when you watch a tragedy, let’s say you’re watching a tragedy that happens in a play where you see an actor or a living actor. You see the actor, the actor in your presence immediately. And he is projecting onto you. You are kind of on-screen and there is a synergy.

There is a kind of a relationship between, presence between your presence and the actor’s presence on stage. And now in and Stanley Cavell, it raises the discussion because he’s talking about, what gives us pleasure in watching a tragedy? Like why do we like watching tragedies? It’s so terrible. It’s all its pain and suffering. Why should that be esthetically pleasing in any sense whatsoever?

And many philosophers have tried to answer this question. And there are all kinds of answers. But I still think Stanley Cavell is the best one. And he says in the theater when you’re watching, take the case of Othello. You’re watching Othello strangle the Somoza Desdemona. You’re watching a man strangling his wife on stage in front of you. Yeah.

What the theater allows you to do allows you to see a horror played out right before your very eyes in your living present.

But the convention of theater makes it such that you are not supposed to respond. You see that and we get kind of some enjoyment out of that. In a way. I could call it a pleasure movie. Pleasure is kind of not the right word, but that is why we go to kind of test or elicit these kinds of responses to see how we would react, knowing full well that we are not required to. For example, if you were actually in real life in a cafe and you looked over and you saw a man strangling his wife or throttling his wife, what would you do? Do that experience? Probably, right.

I mean, this is something you would never think about unless it happened. But if you saw that happen in real life, that wouldn’t be pleasing you. Wouldn’t you want to know? Like, there’s just no way do you intervene. You do not intervene or damned if you do, you’re damned if you don’t. But the theater takes that.

It takes that away. You don’t have to. You’re not supposed to act at all. You’re just supposed to watch the same thing. And I think that’s true. Now, in the movie, like in a cinema house, we are not present to the actors at all. We are mechanically obscene, to put it this thing to come out. But there’s a projector and there’s a screen and the image is projected onto the screen and we watch movies in the past tense.

You know, there is not this direct participatory element and movies are already and you know that they’ve happened. But in the theater, something is happening in our present.

Jeff – That in real-time. Right.

Amir – Right. In real-time. Yeah.

I mean, and you could say, well, we know the act up there. There’s not strangling his wife and we’re not and is not. We know it’s just an actor. I mean, you could say all of those things. But what it doesn’t take away from the fact that there is a real human being and there is a real horror.

And if you let it, it will elicit the same type of response to this as if you were, you know, sitting in a cafe and you watching what’s been happening. But that does not happen in the cinema, because we are not there is that participatory element that is lacking. So why that matters too much discussion again, is how I was thinking about this book, is whether or not theater can do what you can to make us feel, the living presence of the actors that are on screen.

I guess my conclusion would be it’s not quite the same. It’s not quite capable. But by the conventions, the cinema can enhance through the deployment of irony. It can you can relate to such a sense and meaninglessness that is so profound and so deep that it comes close to the theater, knows it’s a tragedy. So it does what theater does tragic irony and violence.

And it exposes a sense of meaninglessness, the same sense of meaningless we feel when you go to the theater.

Jeff – Well, the next time I go see a play, I’ll think of all of that because that was fascinating.

Movie- 6. Be kind Rewind, with Jack Black, one of my favorite comedic actors. And you say as a medium, as a technology, of course. Now, this is a while back because now we have DVDs and a lot, Netflix streaming. But anyway, you wrote as a medium as a technology videocassettes are all the people have not to create a civilization for themselves first but to see themselves first. And then you talk about the there was a lot of philosophical discussion about, the difference between TV being a small screen and cinema being a big screen.

And how do you compare TV cinema? And what I just talked about that we can change video cassettes to DVDs now or in Netflix live streaming, or are all the people have not to create a civilization for themselves first, but to see themselves first.

Amir – Right, the difference between TV and cinema, I think it’s an interesting question and I think that’s a great end in this film. Be kind Rewind. One thing that kind of seems like a silly question prima facie. What’s the difference? OK, if I watch a movie on the cinema screens and then it’s playing us it’s doing a run on a television network. And I watch it, as, you know, like a television show.

Is there any difference in experience? Know ontologically and I’m not sort of interested in, you know, whether it’s a different thing when you see a movie on your home TV box or do you see it on a big screen? I am now interested and I think that this movie is kind of addressing that question uniquely in the media or the media that is used to watch whatever story it is that we consume about, you know, what we take to be maybe our lives or maybe about other things as well.

But whenever we watch movies, what medium are we used to watch them? Now, of course, we use film, and I use it.

They talk about Harold, he’s a communications theorist, Canadian communication theorist, and he talks about how the type of media has ramifications on how he receives the content. You know, Marshall McLuhan also talked about this. The medium is a more important message. And what’s interesting in this movie, because rewind just again, a little bit of a primer, maybe some people who are not familiar with it.

It’s to be kind rewind videos and, you know, they rent video cassettes out to customers and so the mike is running. And his uncle is Opsahl or his father-like figure in the film played by Danny Glover. But he’s Absent-Minded is sort of running the stories instead. And there’s some sort of electrical accident that happened at the local power grid. Jerry just played by Jack Black and gets kind of electrocuted or whatever, but he’s electrocuted and he walks into the video store for some reason. Somehow he raises all the video. So that’s like playing the tape. Yeah.

And to save face mike come up with this idea like played by most. Mike comes up with this idea where he’s going to record by himself, him, and Jerry. They’re going to recreate all of the films themselves, some props. Jerry is the proprietor of a junkyard. So they find all these props and they start shooting all of these films themselves as a kind of a stopgap measure because they think maybe, OK, nobody will notice. But of course, this is a process that eventually comes to be known as sweet reading a film.

So the idea that you just kind of you remember the film and you kind of recreate it reacted yourself with your props, you know, in it among the community. Just put it on video. I mean, the idea is constipating. I don’t know if Sweeting ever took off on kind of phenomenon in real life, but it’s kind of an interesting idea about the malleability of a given medium. And you remember just because. That’s right. So it was always this idea like you could tape over star stuff. Right.

Jeff – Right. Yeah.

Amir – It’s not quite the same. Right. I mean, I don’t know there are rewritable DVDs, but like or even with live streaming stuff like that, there’s no chance whatsoever for you to record over Summerson. And what I think that record Macau to be in, because everyone is the type of participation nation through the Swedish media, the whole community. And that film comes to lifelike. So not only do they figure out that the movies are been sweet, they like it because they are now telling the story in their way.

We talked about, you know, novels requiring active imagination, as a medium, as an art form, and cinema is much more passive. You just sort of you just receive passively. Perhaps you don’t participate in any way. We imagine that the imaginative work is done for you, but this is a very interesting play, is proposing an imaginative way that people could participate in the stories and give their lives meaning. You know, Hollywood movies could participate at a local level.

And I think to me, that’s kind of a very old revolutionary, kind of thing to do. It’s kind of really interesting because it gives art that we consume rather passively than that interesting participatory element. Of course, it’s all fiction. It just never really happened in the movie. What’s interesting is eventually the studio bigwigs from Hollywood to get wind of what’s going on in Pacific Jersey, a town that doesn’t matter to anybody. They’re just doing this stuff on their video store, whatever they get, the wind of it.

Hollywood gets wind of it in this very sad scene. You know, they take all the videotapes and they put them on the road. And Sigourney Weaver there, she’s the person from Hollywood studio suits and she just orders a steamroller and or whatever and the steamroller discretionary videotape and so says this is so terrible.

This cultural energy is just obliterated and destroyed by copyright law or whatever. But I mean, they’re not harming anybody. They’re not hurting anybody. But I just thought that was an interesting way and an interesting comment on media medium and trying to make films, do something that they’re medium in itself doesn’t usually think allowing them to do.

And of course, now is moved to DVD from VHS to DVD, and now it’s like live streaming stuff seals off any participatory element even further. Yeah, it’s certainly more we’re much more passive now than if we have more passive consumption of VHS. I thought that was all very interesting.

Jeff – Yeah. So I’d like to watch that. That sounds good.

Movie – 7. Hamlet. And in it, you talk about Friedrich Nietzsche was the first to recognize that Western culture has achieved a type of liberation resulting in willingness for its own sake, that at the heart of the Western cultural experiment is revealed a naked and stark desire for power and domination made possible by platitudinous bromides to progress science and technology as if these forces contained an ethic.

Sounds that seem to kind of get to the heart of Western imperialism and colonialism. Tell us what you think about that.

Amir – I agree that you know what you’re saying, and I think Nietzsche was an interesting guy in that regard. He had some interesting thoughts. I mean, what did he say?

He said that all that is revealed is willing naked. And we don’t know if we don’t have any ethics that constrains them. Or so we have to kind of embrace women’s birth and say so with the will to power, but we can’t do that because there is still a residual ethic. And he says this comes from the ancient world, from Socrates, mostly from Christianity. Of course, he didn’t like Socrates very much and much. He didn’t like Christianity very much because Christianity brands this will to power itself evil.

And we kind of have to get away from that. We have to stop thinking about the people to embrace even our self-destructive tendencies, which is something which I think the ancient Greeks were able to do. That’s why they are the highest civilization they should ever have anyhow.

But Nietzsche also says that human beings thrive within a horizon. So there has to be kind of acknowledged limits in a way, for us to thrive and do it, do what we want to do.

But at the same time, human beings, because now God is dead. We know that all the horizon that we create for ourselves, I think, you know, we know that they’re not real. We’re always looking to overcome these horizons right now. We don’t like things. You know, I think that we don’t like things like theology or philosophy or the humanities as subjects because they’re attempting in a way of impeding the forward march of technology.

And, you know, just the idea of technology as an assumes good because religion or anything like that when God is dead and there is no stable idea of the good, you know, what is just generally good? No, there is nobody. No institution can define what is good for human beings to do or not to do. They don’t have any influence at all. Anybody who attempts to do this is kind of a cultural relic of some kind. So and there’s kind of a vacuum there of what constitutes good.

And I do think that in our society, what fills the boy is immediate, of course, is technical knowledge. And it extends from this idea, you know, the classical idea that the highest good in man is rationalities. You know, it’s why nature didn’t like it very much when Socrates did that enough. And rationality, of course, gets eventually tied to like science and science and technology, go together A equals B equals C rationality, science, and technology.

These things are all just good. You know, we can do it. We figured out how to do it. So if we can do it, why not just do it, you know? And but we have no way of asking ourselves. Another type of question was wait. Is it really good to do this? Should we do it?

And, you know, two examples you can talk about like we have the technological capability of doing something like fracking or genetically modified food.

Right. And so there’s OK, so if we can do it, should we do it? And when we make the case that we should do it, we appeal to all kinds of horizons. I know like, well, genetically modified foods, if we pursue this technology will end world hunger one day or, you know, we will increase crop yields or whatever. So it sounds good. You know, it sounds really good to say, OK, I can get on board with that. Let’s do it. But we’ve been doing genetically modified foods. For how long? 50 years at least probably more.

And we haven’t done anything about world hunger or anything like that. No. So we know that horizon. I think we kind of try and draw it for ourselves. But why do we do it? Do it for power and domination and profit. That’s it. That’s the only reason being told on all of these. That’s the only reason we were selling all this stuff, is there’s no ethic, there is no estimate. And this sort of willing where they sort of drive endless.

And when we realize that nothing is constraining all of our mad pursuits of technology, a darkness kind of falls upon us as well as George grants Guangzhou and that is a vision of violence now going to have to high.

What does this have to my claim is that in Hamlet, to Steve Coogan who plays Dana Marschz, who is a high school drama, instruments, he’s Horizon Island by the cultural influence of Hamlet? So similarly, when we talk about something like Hamlet, we don’t even know why we need Hamlet, him or if we should remember him. But like the anguish that the main character expresses in the head with to it, he says why? What’s so great about Hamlet? Everybody dies.

Realize that the tragedy and what he wants to do on stage. And he doesn’t stage Hamlet to the West Mesa High School. He teaches that the stage seems to have a general by William Shakespeare. He stages Hamlet Do, which is kind of like a cold response. And he’s trying to express his bewilderment and he’s just trying to say, like, we need to get beyond the don’t forget that. Because we don’t know what it’s for, we don’t even know why we’re doing it.

We have no way of addressing whether or not Hamlett is good. Like what? What if Hamlett had it good or if there’s any possibility that it’s left in that plane? First of all, that’s a good question.

Is there any possibility left to be explored that hasn’t been explored? You know, haven’t we read and talked about this play enough and talked about it for the better part of 400 years?

Are we anyway doing and if not, why did we did it in the first place? And I think at the end of the movie, there is this kind of also this cathartic failure. There is a catharsis and it’s kind of a very feel-good, warm-hearted kind of movie. And at the end of it, that’s sort of kind of warm-hearted in that way. But it’s also, I think, it’s meaningless, meaning that the climax of this kind of ridiculously, loosely, absurdly ugly meaning people over to particular ends the book.

Yeah. So I think that’s really what I thinking after watching that movie is number one, did we ever have to have first place? And number two, we managed to get rid of it or if we managed to get rid of them, what next? Where do we go from that? We don’t know.

Jeff – What’s the encore, right?

Amir – Yes, we have no clue. And that again is like I say, as a vision of nihilism. And so the movie brings us it doesn’t have any answers, you know, where we should go, but it brings us to the precipice in a very intelligent way.

Jeff – Amir, this has been an amazing interview. I never had a guest on the show who to discuss something so cultural and after I read your book.

You know, I’m starting to like notice, you know, references to movies and stuff, you know, in the popular press and the news, you know, like with that Martin Scorsese and Francis Coppola, where they were, you know, Disney Marvel Comics. And I’ve started to notice just how impactful the cinema is in our daily lives.

This has just been a superb discussion. Thank you so much. One final question. What do you have in the literary journalistic pipeline these days? I know you’re a busy professor, but have you got some sideline projects for yourself?

Amir – Always. Yeah, right now I have a second book of literary criticism I’m working on in Shakespeare’s Roman place, so close reading again of four plays, Timon of Athens, Coriolanus, Julius Caesar, and Cleopatra. And I’m also trying in earnest to now write on Chinese cinema. And I’m currently working on a reading of the wandering art, which I think is just marvelous.

Yeah. And I discuss the ways that this film is sort of ingested aspects of technology fetishize from the West and but at the same time, I think it also provides a very able critique of that.

Jeff – I don’t want to say I got them legally, but I have about 130 Chinese movies downloaded and I spent going back to the 1930s I took the Shanghai. Oh, what’s that magazine called that all the ex-pats read that’s in all the different big cities.

But anyway, I took their hundred top movies that they ranked and I was able to find most of them or almost all of them online. And then I went to the trouble to go to sub rip websites and found the English subtitles for probably 85 percent of them. So if you want to have a crack at those two, I’ll send you the hyperlinked.

Amir – Yes. I’m coming to your house right now.

Jeff – I’ll just put them on the cloud and you can get them in early on. And because I love Chinese cinema, it’s so gritty and real.

Amir – I agree.

Jeff – I think it’s fantastic. I so much better, I think, than a lot of Western cinema. But anyway, so I’ve got like 120 movies and I think I probably have subtitles for maybe 90 or 100 of them. So I’ll send you a link for that, for your research.

Amir – Wow. Thank you so much.

Well, listen, thank you so much, Amir, for coming on. This has just been super fascinating and I will never go see a movie again with the same eyes. And I have you to thank for it. And I think a lot of our guests and fans out there will feel the same way. Have a wonderful evening and I’ll let you know what this is up. And you can share it with the world.

Amir – It was my pleasure being on. Jeff, thanks very much.

Jeff – Bye-bye.

Amir – Bye-bye.

###

Why and How China works: With a Mirror to Our Own History

JEFF J. BROWN, Editor, China Rising, and Senior Editor & China Correspondent, Dispatch from Beijing, The Greanville Post

Jeff J. Brown is a geopolitical analyst, journalist, lecturer and the author of The China Trilogy. It consists of 44 Days Backpacking in China – The Middle Kingdom in the 21st Century, with the United States, Europe and the Fate of the World in Its Looking Glass (2013); Punto Press released China Rising – Capitalist Roads, Socialist Destinations (2016); and for Badak Merah, Jeff authored China Is Communist, Dammit! – Dawn of the Red Dynasty (2017). As well, he published a textbook, Doctor WriteRead’s Treasure Trove to Great English (2015). Jeff is a Senior Editor & China Correspondent for The Greanville Post, where he keeps a column, Dispatch from Beijing and is a Global Opinion Leader at 21st Century. He also writes a column for The Saker, called the Moscow-Beijing Express. Jeff writes, interviews and podcasts on his own program, China Rising Radio Sinoland, which is also available on YouTube, Stitcher Radio, iTunes, Ivoox and RUvid. Guests have included Ramsey Clark, James Bradley, Moti Nissani, Godfree Roberts, Hiroyuki Hamada, The Saker and many others. [/su_spoiler]

Jeff can be reached at China Rising, je**@br***********.com, Facebook, Twitter, Wechat (Jeff_Brown-44_Days) and Whatsapp: +86-13823544196.

Read it in your language • Lealo en su idioma • Lisez-le dans votre langue • Lies es in deniner Sprache • Прочитайте это на вашем языке • 用你的语言阅读

[google-translator]

Wechat group: search the phone number +8613823544196 or my ID, Jeff_Brown-44_Days, friend request and ask Jeff to join the China Rising Radio Sinoland Wechat group. He will add you as a member, so you can join in the ongoing discussion.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: RSS

I contribute to

I contribute to