NOW IN 22 DIFFERENT LANGUAGES. CLICK ON THE LOWER LEFT HAND CORNER “TRANSLATE” TAB TO FIND YOURS!

![]()

By Jeff J. Brown

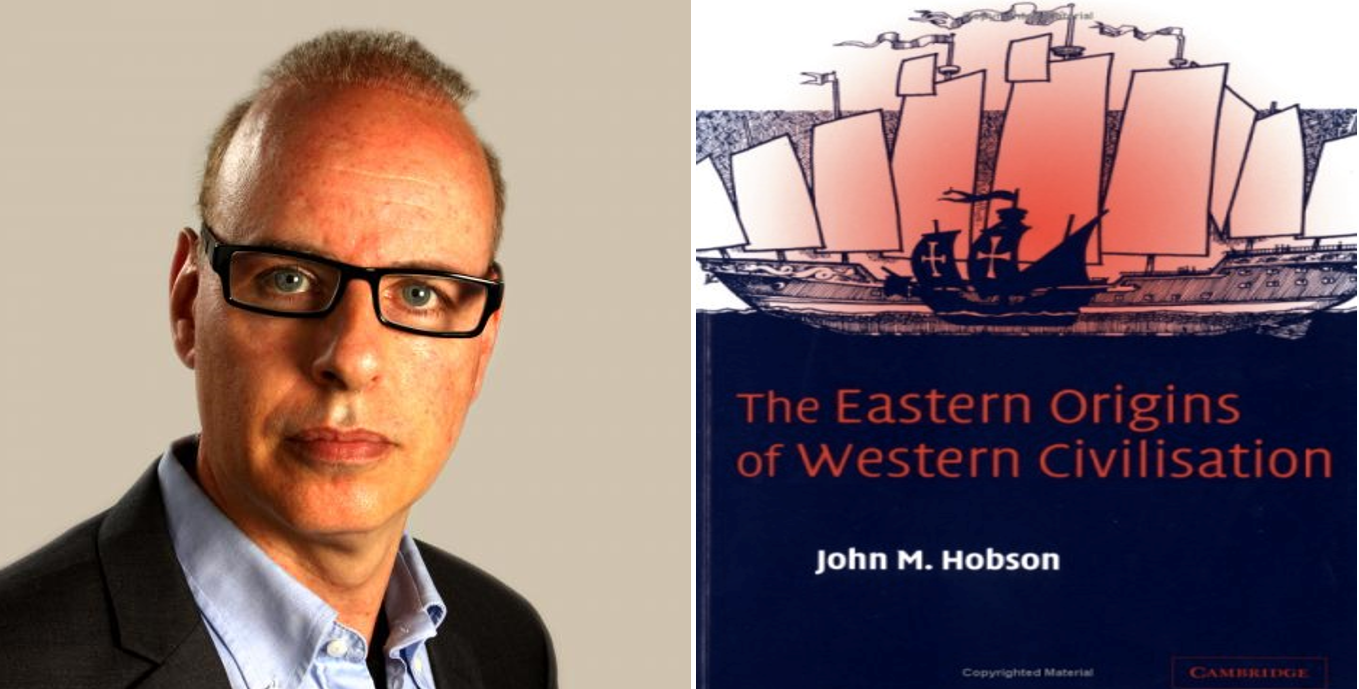

Pictured above: Dr. John M. Hobson and his outstanding book, “Eastern Origins of Western Civilization” (also published in Chinese by Shandong Picture Publishing House (2009).

Do your friends, family and colleagues a favor to make sure they are Sino-smart:

Journalism: https://chinarising.puntopress.com/blog-2/

Books: http://chinarising.puntopress.com/2017/05/19/the-china-trilogy/ and

https://chinarising.puntopress.com/2018/06/18/praise-for-the-china-trilogy-the-votes-are-in-it-r-o-c-k-s-what-are-you-waiting-for/

Website: https://www.chinarising.puntopress.com

Twitter: https://twitter.com/44_Days

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/44DaysPublishing

LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/jeff-j-brown-0517477/

WeChat/WhatsApp: +8613823544196

VK: https://vk.com/chinarisingradiosinoland

Android/Apple mobile phone app: https://apps.monk.ee/tyrion

About me: https://chinarising.puntopress.com/about-the-author/

Sixteen years on the streets, living and working with the people of China, Jeff

For those who prefer reading to watching and listening, here is the transcript of John Hobson’s excellent interview,

Original podcasts: https://chinarising.puntopress.com/2020/05/04/john-hobson-shares-his-wonderful-book-the-eastern-origins-of-western-civilization-i-loved-it-200504/

Interview

Jeff: Good afternoon, everybody. This is Jeff J. Brown, China Rising Radio Sinoland in Chiang Mai Thailand. And I’m going to go north up through the tea and horse routes into Kunming, up into Xinjiang. I’m going to go all the way across the Silk Roads, across the landmass of Asia. Take a boat across the channel and I’m going to go to England and say hello to John Hobson. How are you doing today, John?

John: Very good, Jeff.

Jeff: Well, listen, I’m so glad to have you on the show today. Let me tell you all a little bit about John before we get started.

John Hobson FBA is professor of politics and international relations at the University of Sheffield, having taught previously at the University of Sydney from 97 to 2004 and La Trobe University in Melbourne from 92 to 97. He has written nine books today. That’s four more than me so I really feel like a piker with his most recent one coming out in September this year entitled ‘Multicultural Origins of the Global Economy Beyond the Western-centric Frontier’. His research since 2000 has focused on the critique of the Eurocentric world/global history, which is the subject of Eastern origins, which is what we’re really talking about today, and multicultural origins, as well as the critique of Eurocentric international theory in his book ‘The Euro-Centric Conception of World Politics’.

Wow. That’s John. I just finished reading John’s thought-provoking and enlightening book ‘The Eastern Origins of Western Civilization’. I really regret not finding it until 16 years after it was published as it caused a sea change in my understanding about the history I was taught from my mother’s womb through K-12 education onto university and into adult life with mainstream media. His bibliography put me on to two or three other books that he often referenced, which I look forward to checking out, as well as his 2012’s ‘The Eurocentric conception of world politics’. Listen, I’ve got it right here and I’m going to make sure I’m on the camera and you can see it, I have the book right here. I really recommend that you get this book and read it. It’s a revelation for anybody who is interested in learning about the history of the West and the East. I finished, I was much wiser. You don’t even have to buy it. I mean, librarians in schools and universities and you’re in your place of worship. They love people to make requests and that way everybody gets to benefit from it. They may even already have it because it’s a book that’s known about China. I have his email, He’s not afraid for you to contact him. I have is a Web site and he’s got a few YouTube videos. Thank you for being on the show, John, and being so patient with that intro.

John: Wow, what can I say, it was a wonderful intro.

Jeff: Let’s go ahead and get started. From now on for everybody out there, when I say Eastern origins instead of saying the Eastern origins of Western civilization, I mean, this book right here. When I was two-thirds of the way through Eastern Origins, I finally looked at the back cover to learn that your great grandfather, John A. Hobson, wrote a well-known book in his times Nineteen O Twos, is “Imperialism: A Study.” And please tell us a little bit about his book and did his career influence your professional path, research and in publishing subjects? And that’s kind of like a question one and then and then the second one ‘Is his book still relevant to today’s world?’ Take it away, John.

John: Ok, so let me just say a few things about that particular book. He is a kind of enigmatic figure. On the one hand, he’s really well known for his critique of imperialism, but he’s far less well known for his work on international relations. And in fact, he wrote a lot more about international relations than he did on imperialism. I think the second point about that book is that it’s been pretty well misunderstood and that’s because people think that ‘Imperialism: A Study’ is a critique of imperialism. Hobson was actually pro-imperialist quite what comes out is that what most people do is they read the first 30 per cent of the book, which deals with the economics of the empire that’s where he lays out the critique of imperialism. Third, which is the really interesting bit that hardly anyone ever reads, he looks at racism and culture and a whole series of things which flip a lot of our understanding on its head. So what it turns out is that he critiques what he calls insane imperialism in the first third, that national economic projects of empire in the second two thirds, he lays out a theory that he calls sane imperialism. Sane imperialism is the notion that empires can continue so long as they are independently supervised by obviously an independent international body. And in particular, he was a key figure in the idea of the League of Nations. In 1915, he joined the Union of Democratic Control in that year. He also published a book called A League of Nations, and in particular, his argument was became later understood and known as the mandate system. The Mandate System Article 22 tells us in Parliament that the League of Nations will act as a trusteeship for empire. In other words, it will ensure that the practice of empire on the ground in the colonies would, in fact, be done in the interests of the people therein, the second part of the book really goes into that and what strikes me is that although I would call Jay Hobson a Eurocentric imperialist, much of that second two-thirds was a critique of scientific racism. And if you go back to that period, you’ll find that he, I think, would be one of the first people to undertake a critique of scientific racism. Plenty of people on the left, further to the left of him, such as the webs, were very pro scientific racist. Sidney Weber’s eugenicist, in fact. So he was a figure before his time and a lot of what he did has not really been more widely appreciated and as his great-grandson, I feel it incumbent upon me from personal reasons for bringing this out.

As to your question ‘Has he influenced my work?’ Gee, that’s a great question and it’s really hard to answer, my PhD, I don’t want to go into this in a lot of detail but essentially was looking at the rise of the protectionism in the late 19th century in Europe. And the argument was that states raised tacked tariffs not to protect the dominant classes or economies, but because they needed tax revenues for military purposes. And so that came out as a book called ‘The Welfare States’ back in 1997. And then the funny thing is that in 1998, I had to do the research for a textbook that came out in 2000 ‘state and international relations’, and in there is a section on Hobson and that’s where I became aware that in Chapter seven of his book Imperialism, he made a very similar argument to the one I just made in my PhD.

Jeff: And you didn’t know it.

John: And I didn’t know it and I regret only finding that out a year later. And also his critique of scientific racism and what a lot of my 2012 book was on exactly that ‘The Euro-Centric Conception of World Politics’. But again, I only really became aware that in its detail when I was doing research for that book. So maybe when I read the whole of imperialism, that triggered a lot of ideas about the critique of scientific racism, which then later became put into my 2012 book. Maybe, but it seems that it’s more subliminal than it

Jeff: So it sounds like his book is still relevant today. I mean, if you were using it.

John: Yeah, that’s another good question. And it’s harder. I mean, he was very pro the League of Nations and obviously very pro the mandate system. But once it had been established and it turned out not to be fulfilling the task, he believed it should. Then he turned against it. So the question is, while in principle he’d be interested and supportive of the United Nations, you might find that he’d make a subsequent critique of it because it doesn’t fulfil the sort of anti-imperialist project that he wants it to. So it’s really hard to know.

Jeff: Cool. Thank you. Right at the beginning of Eastern Origins, you made it a point to show that Karl Marx and Max Weber were just as homophobic and racist as the rest of them during their lifetimes. Why was it important for you to bring this to your readers’ attention?

John: May I just parlay that question by asking? Obviously, that struck you as perhaps a curious line of attack of logic. I’m wondering why you’ve asked that before I answer your perfectly good question.

Jeff: Well, and by the way, this is an impromptu answer, John and I have not rehearsed this at all. When I read I thought, well is he trying to make sure that people think he’s not a communist or a socialist or something, I thought I thought maybe you were trying to just make sure that people didn’t think that you were a pink, I’m exaggerating but you know, a pinko sympathizer. That’s what I thought.

John: Now, that’s a really interesting observation. I mean, a lot of what I do in the Eurocentric conception book and in that first chapter is, as you rightly pointed out, its critique, left-wing thought, oh, I do that mainly because I’m less interested in right-wing thought, right-wingers will probably be fairly comfortable with being called the Eurocentric, take that judge on the chin, the lefties won’t and if it turns out that they are Eurocentric and before 1945, many of whom were scientific racist, then they’re contradicting their kind of ideological modus operanda and their stand against racism and empire and so on. So I think it’s more important to bring that out for because they would be interested in that. And then maybe they would respond to that. I expect nothing in return from the right-wingers and I’m not bothered written up. And also, you know, there are all sorts of kind of problems with far left-wing thinking when it comes to this whole issue about Eurocentrism and its critique. And a lot of that comes in my new book. So maybe I’ll come back to that but essentially what I was trying to do that actually if truth be told, when I was a student, undergraduate days, I was a Marxist. But in 1995, I did a complete U-turn and became a so-called Vivarium.

Jeff: Oh, yeah. Marx member, okay.

John: You have all the problems of the zeal of the combat who just can’t help trying to get. And then around I suppose nineteen ninety-nine, I read this really interesting book by Brian Turner on Orientalism and Max Weber’s thoughts. And that’s where I triggered the point that Weber was just as Orientalist as in fact Karl Marx was. And that was very much launch pad, coupled with the fact that really I’m a historic sociologist. Yes, I work in international relations and it’s international prison economy and I sort of identified with those disciplines, albeit sort of in a sort of love/hate way, maybe. But I’ve always been a historic sociologist, and historic sociologists gave remarks. But also what I’m trying to do, is signal that I’m not a traditional historian and any traditional historian will tell you that. Historical sociology, not traditional history and so that’s indicating that as well.

Jeff: All right, cool. Well, now I know. Early on you really framed the rest of your book with a wonderful table comparing Westerner’s perceptions of themselves versus Easterners and it reminded me of Dr Robert de Williams Junior in his book ‘Savage Anxieties The Myth of Western Civilization’, where he said these beliefs about non-westerners go back to ancient Greece and even before to Mesopotamia with frightening horror show man-eating women ravaging monsters like in Gilgamesh said to be the first book ever recorded. And on the other hand, is the Chinese’s sense of the other, all those people outside of China were very commercial. And different people, peoples’ were categorized according to diplomatic and trade relationships under the old tributary system. And I’ve studied China’s mythical monsters, and they are almost cute and cuddly by comparison to the West.

Please tell us a little bit about the comparative table you presented and why you think the West seems to be unique in its extreme fear and loathing of other cultures, especially compared to China?

John: Well, that’s a fabulous question and it’s one that I’ve been sort of engaging with. Last five years, and it’s part of the story of my new book. Cheers. This is a big one. All right. Cut it short. What you’re referring to that Jeff is what I call the civilizational league table of the world, where the, in particular, the British, but also other Europeans sort of invented the world through the lens of civilization, barbarism and savagery. So civilization for them was Britain at the top with Europe as well, sort of alongside it, well just below. You had the second world of oriental despotisms, China, the Ottoman Empire, suffered Persia, India. And these were barbaric peoples and societies. And then you had the Third World, savage society, frankly the black world, Polynesia, Australasia. You know, now many people will say that China did likewise. Okay, so the sign-extended civilization was China at the centre, the Middle Kingdom then you had the Second World, these were the sort of barbarians and these were in the tribute system. So you have the inner tribute system, so Korea, Japan and then in the outer system, you have the rest of Southeast Asia. And then the third world would savage the world again and this refers to the Mongols, the Europeans, the Manchus and so on in the nomadic societies on the western and the northern frontiers. So they appear similar and many people in the West assumed that roughly the same and some people say that China was just as racist as Europe was. But there’s a fly in the ointment here, First of all, the European or the British league table was based on rationality. So civilization was the most rational. Second world of barbarism, less rational and third world of savagery, a totally irrational. With the sonic standard, it was how Chinese you were so China was obviously the most Chinese, the inner tribute system, well they were sort of Chinese aspirants. The outer system, yes no Confucian elements, which is the definition of Chinese in this league table but also they had other sorts of ideologies such as Islam. They were linked to cotillion, the Mandala systems and so on and then the savages were the least Chinese. But the key difference is this, from what I can see. And I’d be interested in your thought at some point. But is that in the Chinese league table? They were more than happy to treat the savages as well as the barbarians in inclusive terms, they could cooperate with the Mongols, Fantastic. That’s what they wanted. The problem is that the Mongols would not always reciprocate. And eventually, after all, sorts of invasions and constant, you know, raiding parties. The Chinese got fed up between 1683 and 1760, China nearly tripled in size as it took over the western province, which became Xinjiang and the northern provinces which became part of greater China, which were the old Mongol Manchu European territories. So there was nothing inherent in assigning standard that would lead to imperialism. Imperialism in the Chinese context was a defensive military strategy. I’m not trying to legitimize it. I’m not saying it’s a good thing. But that was the logic.

Think of Britain rather like America today, surrounded by sea. Nobody was trying to invade it. Certainly not from the non-Western world. It was secure. By Chinese logic, it would not have colonized anybody, but it did. So what happens in the British standard, in particular, is that if you are deemed to be savage Africa or Australasia’s, so you will be colonized. That’s not the case in China. So I think that they are ultimate, despite the superficial similarities, very different. Now, as to the question, why were the Europeans just so fearful of non-Western cultures? That’s a big question. It’s a great question. It’s really, really important. I sort of think of that question also in the context of the United States. And I think that there are parallels here. So for me, that kind of racist mentality, which is always equated with this so-called conception of Western supremacists, is really just based and I don’t think this is rocket science on an inferiority complex or an insecure. Now if you think of America today, in many ways, frankly, the greatest civilization on earth, surrounded by sea with friends to the north that they make gentle jokes about and then Mexico to the south. They couldn’t be more secure and yet you watch their films and they’re all about the latest threat to America, A tsunami coming, a volcano erupting, a disease come across, a meteorite from outer space, It’s got to be blown up by a nuclear bomb and so on and so forth. You know the most significant civilization on earth is possibly the most paranoid, probably even more paranoid if you can measure these things than Israel, which is genuinely surrounded by hostile states and a similar thing happens in Britain and Europe. Why?.

You go back to the Roman Empire and ancient Greece, these were impressive in their own context civilizations and then what happens? We go into feudal Europe, backward, stagnant. The dark ages. And there would have been a sense of civilizational loss. Just like the Muslims today. Islam was an incredibly impressive civil from 800 through to fifteen hundred. It was in many ways the leading civilization in the world, perhaps by China. And yet today, having declined, particularly relative to the West, they feel that sense of loss and it’s that sense of loss. And that sort of inferiority complex produces, frankly, awful outcomes. The most difficult people to deal with in society often are not thugs, but the people who are really insecure because they can do weird things. And that’s what I think. I mean, this is very generic. I think sort of going on here which is why Europe became. It protested too much superiority always goes along with an inferiority complex. The Chinese were by historical standards, an incredibly impressive civilization, incredibly inventive that the East Asian and Southeast Asian regional systems were remarkable for their peacefulness. And yet, look at Europe. It was like the warring states constantly at war. They were comfortable in themselves. They had a very impressive civilization. There was no need to prove themselves in that way. And I think it’s somewhere along those lines that the difference.

Jeff: Very interesting. Thank you. Robert Temple’s book, which I have in the living room and keep next to yours called ‘The Genius of China: three thousand years of science, discovery and invention’ makes a nice companion piece to your work as it catalogues one hundred Chinese innovations. What one comment of his really jumped out. Dr Joseph Needham, upon whose work Temple’s book was based, estimated that no less than 60 per cent of the West’s technology and invention has sources in China. Your more detailed study really brings this to life. What is it about Chinese history/people/civilization that made this so.

John: It’s tough to answer, Jeff. I have absolutely no idea. I’ve read a lot of the Needham stuff, so I don’t know how many, 20, 25 volumes, average five hundred pages, I’ve read an awful lot of them. I don’t think even broaches that question. It’s an enigma. But one thing I wondered about. Let me know if you think this is worth a brief discussion, I’m going back to the Needham question, Some people say, well, if China had been so inventive, why didn’t it industrialize? And if Britain, which had been a laggard visa v China for 2000 years, it managed to industrialize. Why is that the case? And many people would conclude that the British in the end are more inventive than the Chinese. And I have all sorts of arguments in my new book as to why I think that’s not the case. I think in the end, they didn’t need to, they advanced civilization, they led the world in cotton textile production, which was the most important sort of so-called manufacturing industry at the time. They had no need to mechanize technologies like the British did. The British had to mechanize cotton technologies, had no choice if they wanted to be able to deal with Indian cotton textile exports, which were like a tsunami across the global economy. So they had to. Yes, I think they have to be given credit for coming up with these technologies, the water frame, the mule, the spinning Jenny, the power loom and all the rest of it. That was impressive.

But the Chinese also had something called the big spinning frame for Ramie, which they invented in the 13th century, and then later went out of fashion after the 14th century. This is because the Chinese started to wear cotton clothes after the 13th century and Ramie based plant went out of fashion. Now I mention this because this was a mechanized spinning frame, albeit spinning frame for Ramie, not cotton. The difference is the cotton needs to be drawn out. Ramie doesn’t. It just needs to be twisted and spun. And because it didn’t have to drawn-out, there was no drawback. So the question is, could they have invented the drawback? Answer yes. They, in fact, did have such a notion of a drill bar. They used it when they were spinning five Roebling’s because you don’t have six fingers to hold the Roebling’s. So they used it then. So the point is that I think that they could have invented a cotton textile spinning a cotton spinning machine way back in the 14th century if they’d wanted to. They didn’t want to do it because to do that would have required three people to operate the machine. And this was all done in households where they couldn’t spare the labour-power for it. So they dropped in. So I don’t think it’s true to say that the Chinese were just not sufficient inventive that they couldn’t have undergone an industrial revolution. In fact, I think they could have. But there are all sorts of other reasons why they didn’t.

Now I have gone off-topic and I guess I’m slightly embarrassed because I couldn’t answer your original question.

Jeff: Don’t worry about it. You just read about what you know, there are steel and iron. And it’s just like, bells and canals and infrastructure and you’re just like going and while at the same time, Europe was just literally like practically swinging in the trees, just how, what is it about them? It’s a question I deal with all the time, too, in my head and I’ve written about and I just wanted to kind of get your feedback. Yeah, it really is In your book the Europeans appear to have invented very little for themselves, and we’re heavily reliant on non-Western inventions. You did list three, though, that the Europeans did invent totally independent of anybody else in the world, The Archimedean screw, the crankshaft camshaft and alcohol alcoholic distillation process processes. Do you still maintain this view?

John: Good question.

I think if I’m being self-critical of its margins for the moment, I think that one of the problems with that book is that it underplayed Western agency, by which I mean it underplayed Western Developmental Agency, a Western inventive agency in a sort of effort to really emphasize just how many of these technologies they like to claim to invent had actually been invented by the Chinese or other civilizations well before. So I think now, in the new book, I want to give them credit for, the industrial-technological inventions that they came up with. And, yes, they borrowed some of these ideas, I’m sure, but they took them to much higher so-called industrial ends. And I think they should be given the credit for that. But that argument if you look at, say, Europe before sixteen hundred, you’re going to struggle to find much they came up with that at least hadn’t been invented before. You’re going to struggle and you’d have to make the argument, in fact. Well, maybe they were invented in China or Islam or wherever. But that was it was coincidental that they came up with it themselves. And at least that’s how Eurocentric thinkers, they always default to that proposition, in part because they can’t always find an archetypal paper trail that that shows how some of these technologies came across.

And in the end, you have to use a sort of other approaches to tackle that question, which I won’t go into. But Europe was a very militaristic civilization, as we all know. But as I said in the book and Joseph Needham and others have gone into this, the first gun was invented in China before thirteen hundred. The first cannon was invented in China. The military revolution really began in China. And it was later diffused out to Islam and Europe. And they didn’t really have much to it until you get into the 19th century. So I would sort of half maintain that proposition for the priest, 16 or even 17 hundred eras.

Jeff: I really appreciated how you not only covered China but also wrote because the book is Eastern Origins is not Chinese Origins, a lot about the contributions that Africans, Indians and Muslims made to Western advancement to make up your Eastern origin theme. For me, it’s also personal, I lived and worked in Africa and the Middle East for 10 years and I became fluent in Arabic in gaining much respect and admiration for the peoples of these gigantic historic regions. Some of the notes that I took. I loved your comments about one black African philosophers giving lectures in Spain and the Africans advanced trading and logistics systems. Number two, Islam’s, fabulous civilization, not just being static librarians who stole Greek works but greatly improved and expanded on them and three, how India’s pre-colonial economy was so sophisticated and capitalist. Not only that, but they all worked and traded together along with China centuries before Europe began to dominate the world after eighteen hundred.

Please tell us a little bit about the huge contributions Africans, Indians and Muslims made to the global economy, science and technology.

John: Wow. To answer that satisfactorily, Jeff would be a recount of Eastern origins and my new book. I really appreciate the question

Jeff: Sum it up.

John: So I can’t go through all of the details, obviously. But what was significant are some key moments like a renaissance in Europe which happened roughly sort of in the 15th century in Italy. Ideas about a man being a rational actor and starting to sort of go away from a God-centered universe and new ideas, philosophy, mathematics, geography, astronomy, all sorts of things. Much of this came from Islam. Now, that’s a big time. But we know that these ideas began in Islam. And it might have just been a coincidence that the Europeans also happened upon them, except for the fact that Europe or so-called Europe. It wasn’t really Europe in those days. It was Christendom. Europe was significantly linked with Islamic West Asia. And don’t forget the Luthien Spain from the 8th century through to 1492 was ruled by the Muslims from Sicily to after 902. There are all sorts of direct links and these ideas came across and so it’s not just a coincidence. Plus, we know the European rulers, the Spanish in particular, would employ sometimes Jews to translate the Islamic ideas for their benefit. Now, what you’re essentially have done is they gone back to that and they said actually all that the Jews were translating with the original ancient Greek texts. So the notion is that after ancient Greece had subsided, a lot of those texts, those philosophical scientific texts ended up in West Asia where they were kept and so that’s the notion that the Muslims were librarians.

Jeff: I love that metaphor.

John: Holding European thought and then the Europeans could borrow from the library, their original book. It’s just there’s no doubt that the Muslims were influenced by Aristotle and by all sorts of other thinkers. But they took them much further and so chapter rights of Asian origins goes into that. For example, mathematics was a really big deal in the Renaissance. That was an important part. Think of Leonardo da Vinci. Right. Now, just a few key bullets point to bring home the point. The term algebra, for example, we all take for granted. That actually came from the translation of the Islamic thinker, Al-Khwarizmi book, which is called ‘al-ğabr wa’l-muqābala’. Al-gabr was translated in algebra and Al-Khwarizmi’s name was translated into algorithm, that’s where these concepts came from and a lot of work was done on this. They were very advanced mathematicians in the in West Asia. Now, they also borrowed from India because the idea of nine numbers and zero, a small point came from India. And we know we’ve got circumstantial evidence to prove it because Al-Khwarizmi actually wrote a book in 825 called On Calculation with Hindu Numerals. So you can start to see a sort of the emergence of a global melange of our ideational flows and then they came across to Europe and they were translating and so on. Ibn-al-haytham was the guy who really set up the optical revolution. That then became embedded in the Renaissance to the notion of perspective. So if you think of paintings in the feudal era, you’d see a huge man on a tiny little ship, there was no perspective because it was all related ultimately to God and it had a Christian framework. That notion of perspective came from Ibn al-Haytham but it goes unacknowledged by Eurocentric. So have managed to sweep all this under the carpet to create this pristine image of a uniquely inventive civilization. And I might come back to this, forget the chance.

Ultimately, what my work is about is not about cutting the Europeans and the Americans down to size, not heaping criticism for the terrible things they’ve done in the world. That’s not really my interest. My interest is simply to deal with the hubris and their belief that they came up with everything all by themselves. And why does that matter? It’s not about scoring points against the West. It’s about saying, look, Frank, the rest of the things they gave you that enabled you to become what you became rather than claiming that they’re all backward, barbaric, savage societies that need to be waged in colour, waged war upon and colonized. That’s really what colonized adorned and I could give other examples, the scientific revolution, notion of jihad in Islam before fifteen hundred, all about independent thinking, independently coming to understand God rather than just being told what the priest tells you. Independent about scientific thinking. The notion of science through experimentation did not come from the ancient Greeks It came from the Muslims and then later became implicated in the scientific revolution that apparently Europe only undertook. Europe probably couldn’t have undertaken this without many of these ideas. That’s not to say that Europeans did nothing. They did two things of importance, but they were enabled and it’s that then up it up that I find egregious, that’s what I am riling against and there are so many more things. The one other thing I’d mention and also there were Egyptians, North Africa, part of the Levant, who also helped develop many of these ideas. They’re also Persians as well as Arabs, It wasn’t just an Arabic thing, which is how we always think of the Middle East. It’s Arab, no, it’s Persian as well and you’ve got the Levant and so on. So now the other thing I’d mention is that you can trace this or you can make links between these technological inventions and these institutional inventions and ideational inventions that then were copied, borrowed, adapted and so on by the Europeans. But also there’s a whole series of other things I really talk about in the new book and I just want to signal a couple I talk about. The new book is really about the multicultural origins of the global economy, and I go from 1500 through to the 20th century and I say that is the first global economy existed between 1500 and 1850. And the pivot of that economy was not China important though China was, It was Afro India. Africa and India formed strong trading relations, which then impacted on Europe in particular. For example, the British and the French had to buy up or decided they wanted to buy African slaves who they would then transport to the new world. The only way they could do it is with Indian cotton textile re-export, they’d have to buy Indian cotton textiles from India, and then they have to re-export them to Africa. Why? Because the Africans did not want British textiles, they wanted the Indian one because the Indian one was way superior. Now, this actually goes back to 1500, Portuguese were doing some similar. Bottom line is this, the British naturally became fed up with having to rely on the Indians for this. What they did is they brought in these new technologies and the reason why they brought in these new technologies is twofold. First, they couldn’t produce enough to compete with six million Indian producers, they had a workforce of 220,000 in the mills, there’s no way they could ever compete with that. And in China, it would be equivalent to perhaps 25, 26 million adult equivalent hours per year. That’s a huge amount of people. The only way they could compete with that is to produce new technologies that could produce huge quantities. Plus, the new technology is not just about pumping out bigger quantities. They were also about producing high-quality cotton because of the problem that the British had is that they did not have skilled enough spinners to create the warp. The warp is the vertical line on a frame through weft is traced and the only way they could do that was through machines. So the British were responding to the Indian structural power and the Afro Indian global cotton whip of necessity that kind of pressurized them to do this, that they did it was to their credit and I don’t want to diminish that.

But they were responding to the Afro Indian pivot and the logic that surrounded that. And so I emphasize that because we are told that the global economy was created by Westerner’s. And that’s what I’m trying to bring in.

Jeff: I can’t wait to read your new book in September.

John: I’ll be happy to send you a copy.

Jeff: I had to chuckle when you wrote that the supposed innate genius of the ancient Greeks was the original source of Western civilization yet they really borrowed their inspiration from the Egyptians around 600 B.C, then we moderns teleological jumped back 2500 years and created the myth that the West has been a pluralistic democracy for just as long while much of ancient Greek history wallowed in totalitarianism, oligarchy, absolute monarchy. And you wrote how before the 20th-century, Western governance was not much better, please explain what you have researched and learned.

That was a funny part of your book, I really enjoyed that.

John: Chapter twelve, I’m glad. While I might go back and revise, some of the claims that are made in that book. This is one I wouldn’t revise. As you say, Greek democracy, well it’s a bit of a non sequitur who were the people that governed, It was the elite property holders. Women and slaves, of course, who are treated as irrelevant, second class citizens at best. If you then go through the kind of western relay race of democratic development so the next stage in the process, of course, is Magna Carta in 1215 on that little island called Britain. But actually all that was the elite property holders, the knights, the aristocracy claiming certain political rights. This didn’t go beyond them. So, maybe five per cent of the population had a say, the other 95 per cent had absolutely no say. Then we can beam forward to 1688-1689 in Britain and the Bill of Rights and all the rest of it. Again, we’re told that Britain industrialized through democracy, that is probably one of the most absurd claims. Democracy came to Britain and it was only in 1919 when the whole of the male population was enfranchised, in 1928 when women got the vote. Before then, they had a partial vote. All these decisions were made and they had no say over it. The great United States of America is the democratic experiment par excellence even beyond Britain only really became Democratic in 1965 after two-thirds of the voting rights. Before that, the KKK had sway over the black population when it came to voting. What you find is that really the full enfranchisement of populations was a sort of mid to late 20th-century phenomenon. And yet we’re told, aren’t we?, that we have an image of America being democratic from day one, apart from the fact that the founding fathers, many of them had slaves and all the rest of them. Somehow, if you were black, you were not properly human, therefore, you might as well say ‘We’ve got democracy for human beings. Well, they are not fully human so we don’t have to worry about them’. That’s not a fully democratic country. Believe me, Jeff. I’m not here to denounce that.

Jeff: I am probably more critical than you are.

John: I bet you are and I would say one thing, any civilization that compared to Star Trek, the original series and Robert DeNiro, they’ve got my undying admiration.

Jeff: You wrote that before 1780, Europeans seemed to acknowledge and show appreciation for all the contributions China made to Western advancement. Confucius was a philosopher rock star, Chinese books and culture were all the rage. Then it stopped. The tables were turned. China was expunged from the movie credits and everything that was great and good and the world was claimed to originate in the West. And you used a wonderful quote by Francisco Bay who wrote ‘If we hope to find explicit acknowledgement of such influence in their works, we shall be disappointed. Western writers and inventors plagiarized each other’s ideas shamelessly and we may be sure that they had no scruples in passing off as their own ideas that had come from the other side of the world. What happened in 1780 and why did this happen. What happened?

John: Ok Jeff, another characteristically, really good question, a very important one. I think it was really sort of 1760 through the 1780s where the sort of love affair with China passed. And then we go into this downward slope and suddenly they became a civilization of eternal stagnation that was extrapolated back thousands of years. And yet previous to that, only 20 years earlier, they’d been seen as one of the most advanced civilizations, peculiar to say the least. What I think happened was that, first of all, if you read Sacred Sites book Orientalism, he dates the rise of Eurocentrism to 1750. He doesn’t explain why it began in 1750. And you can see elements that argue that discourse actually going back to 1492 and the whole thing about Francisco de Vitoria, who basically developed a kind of standard to civilization back then, but nevertheless, certainly in the second half of the 18th century, Eurocentrism was developing. Why was it developing? Because Christendom was breaking down. It had undergone an identity crisis and this had been nothing but death by a thousand cuts. The Renaissance started to question the centrality of religion. Martin Luther in 1517 and the Reformation question the Catholic Church and Christendom was effectively the kind of hierarchy with the pope at the top. Then in 1648, you have the Treaty of Westphalia where sovereignty started to emerge in Europe and which basically meant rulers are no longer going to listen to the Pope and do what he required, so the whole Catholic Christian basis of so-called Europe was breaking apart. What that meant was that they needed to develop a new image, what came to be called Europe. Europe didn’t really exist before 1600-1700, it’s Christendom. So that is what led to this Eurocentric identity formation process. Eurocentrism is an identity that Europeans invented in order to give them a sense of self and at the same time gave them, in my view, a false sense of superiority. That’s where you get the civilizational league table, civilization Europe, barbarism second world, savagery third or that’s where it comes from. So this is all taking off at this time. So that’s partly why China suddenly became seen as backward. It was invented as backward at this point. And then they had to revise their previous understanding of China with apparently no inconsistency at all until somebody points it out. The other thing I’d say is that this wasn’t all just wild invention on the part of the Europeans. I’m not saying there is truth in anything that they were claiming, but It’s not a coincidence that if you go back to the British Industrial Revolution, although printing technologies for cotton textiles were developing in the first half of the 18th century, in the second half, of course, we get all the classic technologies, the Water frame, the mules spinning, Jenny, the power loom. And there is a sense that Britain industrialization is emerging and the economic growth is beginning to really seriously happen. And the combination of these new technologies, coupled with this seeming economic dynamism, is what also led them to believe that there was some kind of empirical basis to their civilization or league table because China did not have mechanized technologies to produce cotton, textiles and so on, despite the incredible impressiveness of their cotton textile culture, their incredible impressiveness about iron and steel production, which you mentioned earlier, which really is something this was not done in a mechanistic way. And so when those machines came along and then economic growth appeared with them, I think that’s what also bolstered or confirms their belief that China was now stagnant and not developing. So that’s really my answer to that particular question.

Jeff: Well, that actually speaks well. And you were talking about the European identity, You wrote how Western leaders used Islamophobia to solidify their governance over their countries, not in 2001 with 9/11, but much earlier. It seems like the West’s elites always need a group of people to hate, be it blacks, natives, Jews, Italians, Slavs, Irish, Germans, Japanese, Chinese, Latinos, and coming to full circle Muslims. Please explain this history and pattern.

John: I would go back very quickly to early feudalism in Europe in the era of Christendom. So we’re talking 800 through to about 1500. And at that time, European civilization that came into contact with more than any other, of course, was Islamic West Asia, the Middle East. They were aware particularly during the Crusades after 1095 that Islamic civilization was on a higher plane. There was just no argument, feudal Europe was passing in the dark ages. Islam was basking what Arun Bala calls the bright dark ages when Islam was really taking off. Some people call it the golden age. So they couldn’t claim that they were superior in a material sense, on an intellectual sense. But what happened is that they appropriated Christianity. Christianity was a Middle Eastern religion, but somehow it became the embodiment of Europe and later on, of course, the USA. But it wasn’t a European or an American creation, It was a Middle Eastern one. And what they did is that they used that as a means by which they could portray the Muslims as in some way inferior. So the Prophet Mohammed was thought to vacate the eight’s, I think I’m right in saying the eighth circle of hell, cause the ninth circle was the very bottom where the devil was not. And so they used Islam, the religion rather than the civilization as a means by which they would claim their superiority. And that’s, of course, what triggered the crusades between 1095 and 1291, which incidentally, the Europeans lost in the end. There was a religious foundation for that conflict with the Muslims in this period.

Then we got to 1492 the so-called discovery of America. And again, I think a lot of post-colonial claims are will now receive racism emerging. What another term could we possibly use to describe and delineate the African slave trade? I don’t think that was scientific racism. Scientific racism emerges really in the 18th century and it really takes off in the 19th after the British have already abandoned the slave trade in 1807 and slavery in 1833. It was based more on religious ideas and you mentioned that you might ask me something about this, so I won’t go into that for the moment. And then, of course, we go on to 1750. Religion still counts. And remember, the imperialism in the 19th and 20th century was called the civilizing mission because part of the rationale for that was form Westerner’s to civilize No. Westerner’s through which that would be done through a mission, religious Catholic and Protestant. So while we move into a Eurocentric and centre racist thought, really sort of 18th and suddenly 19th and the first half of the 20th century. And that we also have this issue, which I know is germane to your own personal experience, that the Irish were considered to be barbaric, if not savage. Actually, I think it’s true to say that the Irish were placed in the third division along with the blacks and the underclass and the reason could be far worse. But I think the logic is that the people who were inventing Eurocentrism or scientific racism were social elites. It certainly wasn’t the capitalist class, by the way, which puts a dent in that particular claim. It was mainly elites. They would be poets. They’d be sojourners. Sojourners were not poor people who went to China and other places, they were well-off. They were artists. They were novelists and so on and a lot of them were quite aristocratic or upper class. And the upper classes have a brutal conception of rationality. So that when they look at the Irish, they see them as overemotional and it’s that leads them to claim that they’re highly irrational in the same league as black Africans. That’s what I think the link is there. Gentlemens, of course, they were highly rational we know that, an emotionless. And so they were sort of at the top of the civilizational of civilization, One rung below the British, of course, in the British type. So now the question is, of course, has that all gone away and my argument would be that it hasn’t really gone away since 1945 and I talk about this in my 2012 book is that scientific racism goes away?

Yes. But Eurocentrism remains, and becomes sublimated, it’s what I call subliminal Eurocentrism. So all the old tropes of scientific racism and old-fashioned explicit Eurocentrism become recycled into new terms, appear to be culturally taught. So, for example, no one talks about civilization versus savagery or civilization versus barbarism. Instead, they talk about modernity versus tradition. But it serves the same purpose. No one talks about the American empire. Well, except Neal Ferguson, of course. But they talk about American hegemony, which is leadership and promotion of public goods for the benefit of all peoples. So all these old ideas come back. But a new kind of sanitized term. Some people have forgotten, really, that these terms are just a more culturally a more respectable concept that yields a cultural tolerance. But, in fact, really come back from those original ideas. And you can trace it through humanitarian intervention and all the rest. I won’t go into all that now, but that’s really just a brief potted history of what you ask.

Jeff: Wow. I want to make sure I ask the right question. Unfortunately, it can be argued that much of the great harm the West has done to black, brown, yellow and red peoples are going back to the Crusades, at least can be attributed to Judeo-Christian thought. I’ve never been a fan of the Jewish Torah/Christian Old Testament. My jaw dropped when I read this, you wrote about a key passage that confirmed my suspicions and which can be seen hidden in so many of today’s headlines. And that is Genesis Chapter 9, verse 27, which states God shall enlarge Japheth, and he shall dwell in the tents of Shem; and Canaan shall be his servant’. And so please explain this fascinating esoteric verse. Do you think that this is also a source of Christianity’s pathological drive to proselytize and convert all of its perceived “heathens” around the world?

John: Yeah, I do. It’s certainly something that hardly rolls off the tongue of American leaders today since George W Bush, although, of course, he would see a civilizational Christian basis of everything he does because God told him that. So that particular passage is referring to Noah’s three sons. Noah gave his eldest son, Japeth he was bequeathed Europe and Shem he was bequeathed Asia and Ham was given the booby prize of Africa. And Africans were seen as hewers of wood and stone, but they were highly primitive people. And I’m not saying that the Bible or the Koran could be reduced to some simple imperialist propositions and that they’re inherently imperialist texts. I just think that would be completely wrong. But there are elements that can be brought out and to be used and abused by people who have imperialist projects in mind. And this all sort of fed in later to this Eurocentric and scientific racism discourses in the 18th and 19th centuries, which basically said that Africans were lazy because they lived in hot and arid environments and you could go out the door and there are apple tree and the apples, you could just pick an apple and you could eat food or whatever, no problem. Whereas in Europe, it was cold, wet and frankly miserable and you had no choice but to work hard if you wanted to survive and that sort of became linked into that original idea. So it was that idea fuzzed with other Eurocentric and racist ideas that sort of develop this much further. I think there’s some truth in it. Not in an explicit sense, but the way it’s been used and abused by political authorities.

Jeff: You touched on this a little bit before, you explained and that this was the part of the book that I did not really understand, you explain that Western colonialism, imperialism and racism are distinct from each other. At least that was my interpretation. For me, it’s all one big ball of hell on earth for the global 99%. And I have a hard time teaching them apart and I didn’t really understand well, what you wrote. Please explain your rationale and as you mentioned I was especially intrigued by your idea of scientific or official racism, which came along later in the 19th century. Maybe I’m wrong, I think you just mentioned it in the 18th century, but I’ve got some proverbial skin in the game. My father’s family was 100% from Central Ireland. Cork, Kerry and Canali Counties. I’ve seen supposedly the scientific illustrations from English research journals showing how the Irish are the evolutionary link between real white humans and subhuman blacks, the latter who is then the link to monkeys. Can you tell us how you make a distinction between colonialism, imperialism and racism. And I was fascinated and a little bit mystified.

John: Yeah, I completely appreciate and I understand your point as to why you were mystified. I think because those ideas were only really emerging in my head at the time. This is back in the early 2000s and they only became clenched in my mind when I wrote my 2012 book although there I run dress rehearsal. So let me just take you through a few of those points to clarify what I mean. But before I do so, let me just mention one point. I like your point about the Irish. So, you know, scientific racism, of course, as we all know, came out in the 18th century and proclaimed the blacks were the missing link between humans and apes. And so the black world, the third world of the black world was really just one notch above the Planet of the Apes in that kind of evolutionary trajectory. And then the Irish then claimed to be the missing link between human beings and the subhuman blacks so they’re sort of in the liminal box in the Second World and the Third World.

Jeff: Purgatory, Racial Purgatory.

John: Yeah, that’s right. That one causes elimination.

Racial purgatory, yeah that’s right, and it’s very interesting, isn’t it, because, of course, Irish people are white so you could draw links with the Jewish race as well. Semitism is a really fascinating thing. I’ll tell you this for free. When I was writing my 2010 book, I didn’t read the whole of it, but I read significant chunks of that, Hitler’s ‘Mein Kampf. And I was sitting in my office reading ‘Mein Kampf’ and I had my door open and somebody walked by and he just happened to ask ‘what are you reading?’ I said, ‘Oh, Mein Kampf nonsense’. And he looks at me in horror. His face just went white, so then about half an hour later, we all had to go to a meeting and he suddenly brought this up. I just caught John reading Mein Kampf and I’m sitting there saying, ‘yeah, that’s right’. And somebody said, ‘oh, my goodness me, that can’t be tolerated and we certainly can’t discuss it’.

Oh, no, we need to discuss it. That’s exactly why we need to discuss it, most people don’t know what anti-Semitism is. I have to say, some parts on the far left of the British Labor Party. all debates on this. So it’s really important we understand it. And it’s really enigmatic anti-Semitism, absolutely fascinating. Anyway, let me just try and put some clarity to some of the confusion that you, frankly I’m quite reasonably underwent when you read Chapter 10. So I cut a long story short, Edward Said, he was the so-called founding father of post-colonial studies and his book Orientalism, he basically says in there, Europe created invented the Orient and he basically said that Western-centric thinking is inherently racist and inherently imperialist. Now, when I came to do my 2012 book that looks international theory in the last 250 years, I had a choice. I could say, look, I could try and show if I believe that it’s so Western-centric, but how would you go about that? You could if you take a Saidian approach, you’d say, right. You’d bring out the racism of it and you’d bring out the imperialism of it.

The problem is this, that I came to realize that there are a lot of Western-centric thinkers that really weren’t scientific racists, but they were Western-centric. I also came across many scientific racists and Europe, what I call Eurocentric institutionalists, who were very anti-imperialist. Some of the most awful scientific racist thinkers, the American Lothrop Studdard who wrote the book, ‘The Rising Tide of Color’. Quite an amazing book, I have to say and beautifully written. He was very anti-imperialist, just like Samuel Huntington. And the links between Huntington and Stoddard are really, really striking. I wonder if Huntington ever read that book, but if he didn’t, he did a brilliant job of suggesting that he must have because really that book is about how Western imperialism has been bad and has alienated the browns and the yellows, the Muslims and the Chinese and now they’re looking for revenge. And now the West is having to sort of consolidate itself, huddle in the citadel of Western civilization while the hordes of barbarians, Muslims and the Chinese are barking at the gates, trying to tear Western civilization down. Again a lot of scientific racism is based on an inferiority and insecurity complex, think of the KKK. Anyone who is secure in themselves would not go around lynching black people. That’s really quite obvious to me. They felt threatened the Emancipation Act, then thirteen, fourteen, fifteen sixteenth amendments which are giving black people a say in the United States. This was terrible for these white people because they felt threatened by it. If you’ve been comfortable in your skin, you wouldn’t have had a problem, would you? So you signed a security and you find Adolf Hitler was the most insecure them. He was terrified of the Jews. All this notion of white supremacy, at some level, it’s a mystification because really it’s white inferiority. You know the notion that the Jews were an inferior race has to be navigated against Hitler’s belief that the Jews ruled the world that they were the leading capitalists and some of them were leading communists. But if they’re genetically inferior, those two propositions just do not add up are inconsistent. So what you’ve got, and I spent a lot of actually more time reading scientific racist books than I did anything else because they’re utterly fascinating. What you start to realize is that there is no one scientific racist theory of the world and world politics, there are lots of them. There’s Social Darwinism, there’s Lamarckism, there’s Eugenicism. They’re all different. And they all have different implications for foreign policy and so on.

So in the end, I differentiate between what I call Eurocentric institutionalism from scientific racism. Karl Marx, he was Eurocentric institutionalist but don’t believe he was racist. Adam Smith was your Eurocentric institutionalist, I don’t believe he is racist. Karl Marx is pro-imperialist. Adam Smith was an anti-imperialist. So as a man, you can’t say. You start to get in the end four positions, Pro-imperialist-Eurocentrics, Anti-imperialist-Eurocentrics, Pro-imperialist-scientific-racist, Anti-imperialist-scientific-racist. Then I sort of through that lens, start unpacking 250 years of as many international thinkers as I can possibly find to make that claim. So I’m reducing it to the more complex understanding of these things. But I think it’s necessary because it’s just not good enough to say that all Western-centric thinking is inherently racist, inherent imperialism.

Jeff: It’s interesting to know. Well, I can’t wait for September to get here. Before I ask the next question, we can all offer condolences to Gavin Menzies’s family as he passed away on April 12th at the age of 83, which happened to be Easter.

For 10 years, I did not read Gavin Menzies’s books 1421 and 1424. Because I kept reading in the mainstream press that they were “fake news and full of lies.” And when I finally did, 1421 has in my opinion, more than enough smoking guns proving that the Chinese were applying the world’s high seas at least decades and probably centuries before Europeans left port. 1424 is intriguing but more speculative, that the Chinese sail to Italy that year. Nevertheless, do you agree with Menzies about his first book that the Chinese beat Columbus to the Americas.

Why or why not?

John: Again, another fascinating question. I certainly dipped in quite considerably into that book. I had the pleasure of meeting Gavin Menzies actually in the room.

Jeff: Oh Really?

John: Yeah, at a Royal Geographical Society meeting, which hosted a whole bunch of people, including this lady and I’m prepared to put this up, Charlotte Harris Reese, and she’s also written this book is called ‘Chinese Sale to America Before Columbus.’ And she’s got some real stuff in there, really good stuff.

Jeff: I need to get that.

John: It’s very good.

Now, he is to use the phrase, he was a very civilized and quietly spoken man. And he even cited me in his 1424 books.

Jeff: So I just don’t remember that.

John: You won’t, only I would know.

But, what that book, from what I can see and I’m not an expert in it so I’ve not read it cover-to-cover but from what I can see, their mug and I will recall vividly is that Gavin Menzies actually came to his very late in his life. I think he’d been a submariner prior to that throughout his career. So being a submariner, he understood the world’s oceans and currents. And frankly, you know, I’ve written a huge amount on India and Africa and so on in my new book. And I always sort of come across these passages about the monsoons and the different currents going across India. Never really got my head around it. This man knows this stuff inside out. And what he says is and I think I’m right in saying this, he says a Chinese ship in 1424 had gone rounds across the Indian Ocean, round the Cape of Good Hope on the southern tip of Africa, and then plied up the western seaboard and then around the Cape Verde Islands. There are major currents of water. And what I think his arguments are that this boat got pulled out by the toe to toe tide as it, which took it on an arc whereby it ended up in South America. And that’s how he claims they arrived there. So they didn’t go across the Pacific Ocean. They came around this particular route. And then I think he tries to show all sorts of evidence as to signs that the Chinese have been there. The thing is, in one sense, I don’t mean this disrespectfully at all, but it’s a kind of storm in a teacup because there are other books have been written long before this one which made similar claims. I mean Hans Breuer wrote a book called ‘Columbus Was Chinese’. And if I recall rightly, because I was going to develop some of this stuff, these Eastern-origins, but in the end didn’t. If I recall rightly, he shows that there a whole wave of different groups that had gone mainly from Europe over to the Americas. I think he also makes the claim, of course, the Chinese have done it, hence the title. But I mean, the Vikings that arrived in America around 900. The difference, of course, is that none of them had setups, established settlements there and eventually came to colonize the area that we know today as Uthe united the States of America. But there is a lot of really interesting stuff to suggest, particularly if you look at the wider literature that the Chinese had perhaps gone there well before 1421, that’s Charlotte Harris’s Reese’s argument. So, there is a literature out there that does all this. And I think it’s really fascinating but I didn’t really develop it any further. But the historians have taken hard to Menzies book and delivered some really aggressive critiques of it based on some historian who clearly isn’t and I think that it’s almost like a detective novel this story with grounded in what he thinks is a potential reality. And it’s a fascinating read. And I think that in today’s world, a fascinating read probably has more going for it in terms of book sales than a seriously hard read that nobody really wants to engage. It’s an interesting read. And it’s well-written. It’s a good book in many ways, depending on your standard by which you measure these things. To be honest, in the end, it’s not something that really gripped me sufficiently to do any serious further research.

Jeff: Ok. Interesting, All right. If everybody listened, followed your book ‘Eastern Origins’, we would have to completely rewrite European history and if everybody followed what Gavin Menzies wrote, we would have to completely rewrite Western world history.

But so Eastern origins obviously flies in the face of centuries, if not millennia, of perceived Western superiority over the rest of the world’s peoples. How are you treated at your school and in academic circles? Does everyone stop talking when you enter the campus cafeteria? I remember reading that happening to Dr Joseph Needham after he was censored and banned by the establishment for signing on to the International Scientific Commission report, which exposed the United States’s blatant use of germ warfare in Korea in 1951 to 1952. Being such a contrarian, do you think this has had a negative impact on your educational career as a professor and a researcher?

John: Can I just ask before I try to answer this. When you say being contrarian, ‘has this negatively impacted my career?’

You mean just my modus operandi of being contrarian or do you mean my modus operandi of being contrarian in the context of Western civilization?

Jeff: Well, just the facts that you turn upside down or you turn on its head, the idea that everything good and great and in the world came from the West and you completely say, well, no, that’s not really true. As much if not most of it came from the east, etc. and that flies in the face of Eurocentrism, Western centrism, Western superiority. And I know which is obviously looking at the headlines, it’s still true today. And I just wonder, do people just go ‘that’s Hobson, he’s crazy, he doesn’t like the West or well I don’t know, you just seem to be kind of a rebel or someone who thumbs your nose at the established point of view. And I just wondered how you think that’s perceived at your school and then in academic circles and etc.

John: Yeah, I know it’s a great question. No, if I if I’d been in American international relations department, I suspect there would have been some of that. American IR is very kind of an establishment oriented with close links to the State ate Department, so on. And that’s possible because the United States is the global hegemon. Britain, of course, had been the imperial hegemon before the United States took over. And back in those days, you could find a lot of British thought was very kind of pro-British Empire and all the rest of it. But now we have so-called post-colonial Britain. We have a Britain that has been squared back down to size. And you have this giant thing called the United States America, which is the current hegemon. So there is a space for people to start questioning these things, whereas I think there’s far less space certainly in the US IR department. So I can do that. Plus, if you look at IR in particular, British school IR is often defined as being critical. And a lot of what I do is critical and contrarian, and that’s part of my academic personality. And if Eurocentrism is the problem that I think it is, which does help generate all sorts of conflicts in the world. Imperialism in the past and imperial elements today. If that’s right, then what on earth are academics doing legitimizing that idea? It’s just this makes no sense to me. Surely as an academic, we should be questioning these shibboleths, not being written. Otherwise, we might as well be paid 10 times the amount that we get paid and go work for the State Department. It makes no sense. I can’t understand that.

So in the end, I’m uncomfortable in doing what I do. I’m certainly not out to trash Western civilization or to trash the United States. But that’s not what I’m doing. In my new book, I criticized Eurocentric thinkers, but I also criticized what I call euro fetishists. These are the hard-liners, hard left, post-colonialist, often post-colonial Marxists who say that everything bad in the world originated from either Britain or America. And a lot of the book is a critique about. I don’t believe that is sufficient. And I think that they also ignore some of the things, some of the negative, some of the bad things going on in almost the world, they take or they have the hard-left, the soft bigotry of low expectations, which is basically a rather double standard based discourse, which says they hold the West to a very, very, very high ethical standard. If they slip up on anything, the protest marches are out there. But the non-west, they can get away with murder quite literally. And I don’t think that’s good enough. My politics of all this is rather more complex than just somebody who’s out to trash the West. And as I said, really, I’m coming full circle to the point that what I’m out to do is to critique the hubris of the West. And if we accept that a lot of this came from the north-west orbit, that the Europeans and Americans have taken it much further, which undoubtedly they have. If we can just in the West acknowledge that debt, instead of just claiming they’re all stupid, think irrational, barbaric savages, then maybe we have a chance of making a more peaceful and more harmonious world. That’s really what this is all about.

Jeff: Cool. Well, I can’t wait. So your book is definitely going to make it out by September. I’ve said that before, and six months later, it still hadn’t been published. Are You going to get it out in September.

John: Yeah, I’ve. We have this thing called the RAF in Britain. The research Saxon’s framework you have to submit. And my key main contribution is this book and it has to be out before December 2020.

Jeff: Ok, All right. Well, that’ll be my Christmas present. I’ll ask my wife to buy it for me for Christmas.

John: No don’t. Because I will send you one.

Jeff: Well, listen, John, this has been an amazing interview. I went to blasted all over the world and you’re an amazing thinker and an amazing contextualizer and synthesizer about a lot of elements in the past and the present and the future. So I really, really enjoyed your book. And I can’t wait to see your sequel that you have coming out later this year where you feel like you’re going to rectify. So I have this, I read this even though John may not like it as much as he used to. I learned a lot. I got a lot out of it and get it at your library or buy it. And then you can read his sequel and find out what he learned in the interim.

So thank you so much for being on the show, John. I really appreciate it.

John: Can I just say, Jeff, thank you for inviting me on. And you’ve been extremely kind and it’s been an absolute privilege and just a real pleasure. So thank you very much.

Jeff: Well, if you ever make it to Chiang Mai, the first beverage is on me and if I ever make it to Sheffield, I’ll be happy to buy the first part of English tea.

John: Well, I’ll be more than happy to take you up on both of those.

Jeff: I’ll get this out in the next couple of days and you can share it in your circles. OK.

John: Thanks so much, Jeff.

Jeff: Thank you. Bye-bye.

Become a regular China Rising Radio Sinoland patron and get FREE BOOKS!

Support all my hard work, videos, podcasts and interviews on CRRS via PayPal!

Support my many hours of research and articles on CRRS via FundRazr!

Become a China Tech News Flash! patron and see your future now!

It all goes towards the same win-win goals: unique research, reporting and truth telling in support of the global 99%, for a more just and mutually beneficial 21st century.

In Solidarity, Jeff

Why and How China works: With a Mirror to Our Own History

JEFF J. BROWN, Editor, China Rising, and Senior Editor & China Correspondent, Dispatch from Beijing, The Greanville Post

Jeff J. Brown is a geopolitical analyst, journalist, lecturer and the author of The China Trilogy. It consists of 44 Days Backpacking in China – The Middle Kingdom in the 21st Century, with the United States, Europe and the Fate of the World in Its Looking Glass (2013); Punto Press released China Rising – Capitalist Roads, Socialist Destinations (2016); and BIG Red Book on China (2020). As well, he published a textbook, Doctor WriteRead’s Treasure Trove to Great English (2015). Jeff is a Senior Editor & China Correspondent for The Greanville Post, where he keeps a column, Dispatch from Beijing and is a Global Opinion Leader at 21st Century. He also writes a column for The Saker, called the Moscow-Beijing Express. Jeff writes, interviews and podcasts on his own program, China Rising Radio Sinoland, which is also available on YouTube, Stitcher Radio, iTunes, Ivoox and RUvid. Guests have included Ramsey Clark, James Bradley, Moti Nissani, Godfree Roberts, Hiroyuki Hamada, The Saker and many others. [/su_spoiler]

Jeff can be reached at China Rising, je**@br***********.com, Facebook, Twitter, Wechat (Jeff_Brown-44_Days) and Whatsapp: +86-13823544196.

Read it in your language • Lealo en su idioma • Lisez-le dans votre langue • Lies es in deniner Sprache • Прочитайте это на вашем языке • 用你的语言阅读

[google-translator]

Wechat group: search the phone number +8613823544196 or my ID, Jeff_Brown-44_Days, friend request and ask Jeff to join the China Rising Radio Sinoland Wechat group. He will add you as a member, so you can join in the ongoing discussion.

I contribute to

I contribute to

One thought on “TRANSCRIPT: John Hobson shares his wonderful book, “The Eastern Origins of Western Civilization”. I loved it! China Rising Radio Sinoland 200504”