NOW IN 22 DIFFERENT LANGUAGES. CLICK ON THE LOWER LEFT HAND CORNER “TRANSLATE” TAB TO FIND YOURS!

![]()

By Jeff J. Brown

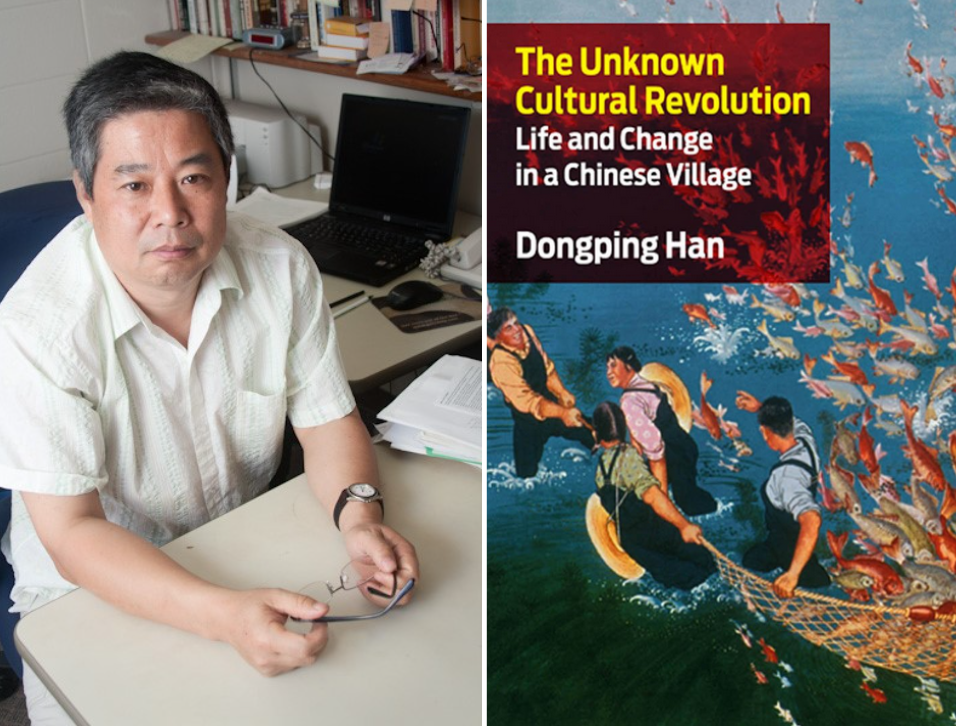

Pictured above: Dongping Han grew up as a child during the Mao Era’s Great Leap Forward, as an adolescent in the Cultural Revolution in a small, rural village in Shandong. He knows what he’s talking about from real life experiences and has gone back to China to conduct ongoing field surveys. Safe to say Dongping speaks with unparalleled authority.

Right here, it takes just a second…

Sixteen years on the streets, living and working with the people of China, Jeff

Downloadable SoundCloud podcast (also at the bottom of this page), Brighteon, iVoox, RuVid, as well as being syndicated on iTunes, Stitcher Radio, (links below),

Brighteon Video Channel: https://www.brighteon.com/channels/jeffjbrown

lMPORTANT NOTICE: techofascism is already here! I’ve been de-platformed by StumbleUpon (now Mix) and Reddit. I am being heavily censored by Facebook, Twitter and YouTube. It’s only a matter of time before they de-platform me too. Please start using Brighteon for my videos, then connect with me via other social media listed below, especially VK, Telegram, Parler and WeChat, which are not part of the West’s MSM Big Lie Propaganda Machine (BLPM).

Brighteon video does not censor and supports free speech, so please subscribe and watch here,

SoundCloud audio:

YouTube is banning and censoring millions of people, videos and channels, including me, so please boycott it and watch on Brighteon above,

Other posts with Dongping Han on China Rising Radio Sinoland,

https://chinarising.puntopress.com/search/?q=dongping

You should also check out Mobo Gao, who also grew up during the Mao Era in a small rural village. I have his latest book, will read it and interview him in the near future,

https://chinarising.puntopress.com/search/?q=mobo

Book Review of Brian DeMare’s Land Wars: The Story of China’s Agrarian Revolution (Stanford University Press, 2019)

By: Dongping Han

Rewriting the History of the Land Reform Won’t Change the History

Brian DeMare’s book, Land Wars: The Story of China’s Agrarian Revolution, was a bold attempt to challenge the established narrative about the land reform sponsored by the Chinese Communist Party, which was supported by the Chinese intellectual community at the time, and more importantly, by the overwhelming majority of Chinese farmers in the last seventy years. It is evident that DeMare underestimated the daunting task he faced in such an effort. What he is trying to do is not just undermine the legitimacy of land reform or the Chinese revolution, but the totality of the history of contemporary China and an important part of the history of the contemporary world. His major argument is that the Chinese Land Reform was unnecessary, and caused too much excessive violence and was unproductive in general. Land reform, or agrarian revolution, through class struggle by dividing villagers into different classes, originated from Mao’s zealous utopian ideas found in his report on the Hunan Peasant Movement published in 1927, was not warranted by the Chinese rural reality at the time. In many rural communities, he argued in the book, there were no real landlords or rich peasants (p 76). But the Communists, locked in the Maoist Agrarian Revolution Paradigm, insisted on dividing up the Chinese villagers into different classes, which were unknown to the Chinese villagers, and caused great harm to the Chinese countryside.

This has been the major thesis of most recent American and Western scholarship on Chinese land reform, Chinese Collective Farming, the Great Leap Forward, and the Chinese Cultural Revolution (1, 2, 3) and a few others which DeMare cited extensively in his book, were all attempts to rewrite the Chinese history of land reform, the collective farming, the Great Leap Forward, and the Chinese Cultural Revolution, in order to de-legitimatize Mao, and his efforts to transform China. There is not much new about this effort. The landlords, the evil tyrants, the reactionary forces in China represented by Chiang Kai-shek and its corrupt government, the oppressors of the Chinese poor peasants, have been promoting this dogma since the Chinese peasant movement in the 1920s. However, they were unable to prevent the Chinese peasant movement from spreading all over China, and the eventual success of the Chinese Revolution. DeMare and others’ efforts to rewrite that part of Chinese History will not go far either.

These American scholars, who did not speak the Chinese farmers’ language, and who were alien to the Chinese farmers’ way of thinking and way of life, came to the Chinese villages, where they were not able to drink the Chinese farmers’ water and eat the Chinese farmers’ food. Their Chinese interpreters, who may have grown up in a big city and like their American professors, had little knowledge about the Chinese countryside, and its history. The Chinese farmers, who met the American professors for the first time in their life, had no clue why these Americans came to their village. They did not know what these Americans were trying to do in the Chinese villages. Some of them did not like to talk to outsiders, let alone foreigners. Why should they talk to these foreigners? The Chinese farmers did not even understand the Chinese urban intellectuals well, and they had more trouble understanding these foreigners’ questions through the translators. At best, the Chinese farmers assumed that they understood the American professors’ questions, and the American professors assumed that they understood the Chinese farmers’ answers. When the book, Chinese Village, Socialist State was finally translated into Chinese, and the farmers from Wugong read it, they were upset. When they heard that Mark Selden was in Beijing University one summer, they came to confront him, accusing him of misrepresenting them in the book. Ralph Thaxton’s book has not been translated into Chinese yet. If it is translated into Chinese, it would be certain that the Chinese farmers he interviewed would have the same reaction: they had been misrepresented.

James Scott, one of the most respected scholars in the field of political science, developed the concept “metis” in his book Seeing like a State (4). He argued in that book that every locale has some hidden knowledge shared by the local people unknown to outsiders. Many grand schemes in our world failed because the designers of these grand schemes failed to understand the local knowledge. The Chinese Communist Leader Mao Zedong, whom DeMare targeted in his book, has stressed the importance of the local knowledge consistently throughout his life. The Chinese Communist Party’s motto: shishi qiushi (seeking truth from the facts) was established by Mao personally. He even went as far as to say that meiyou diaocha yanjiu, jiu meiyou fayanquan (without investigation and research, you do not have the right to speak). He himself spent three months to investigate Hunan peasant movements before he wrote the “Report on Hunan Peasant Movement” (5). He called on the Chinese Communist Party leaders repeatedly to get out of their offices to do investigation and research before making any decisions. He himself was exemplary in this regard, doing investigation and research throughout his life. DeMare did not seem to do any field research for this book, and relied mostly on Ding Ling’s Taiyang Zhaozai Sangganhe Shang (6) and Zhang Ailing’s Chidi Zhilian (7) which are fiction, Bill Hinton’s Fanshen, a Documentary of Revolution in a Chinese Village (8), a few scattered official reports of the land reform, and a few American and Chinese scholars’ questionable books. With his limited knowledge about the land reform, about China, and about Chinese history and culture, the traditional bias of American scholars against Chinese revolution, his attempt to challenge the value and legitimacy of China’s land reform was doomed from the very beginning.

Mao, a farmer’s son, grew up in rural area, and worked in the fields on and off in his childhood. After he left his hometown for schooling first and later to lead the Chinese Revolution, he continued to do rural research. His knowledge and understanding of the Chinese rural society was unparalleled among Chinese scholars and leaders. He stood out among the Chinese Communist leaders and eventually led the Chinese Communist Party to victory in China in 1949 because he had a profound understanding of Chinese rural areas and Chinese agriculture and knew the aspirations of Chinese farmers more than any other Chinese communist leaders or nationalist leaders of his time. The most important reason why the Chinese Communist Party was able to seize national power, beat the U.S. backed nationalists, and became the only one among the several dozen Communist Parties under the leadership of the Comintern, was because Mao understood the issues of Chinese peasants and developed land reform policies correctly to solve the peasant issues in China.

During World War II, American army observers sent to Yenan reported to the American Government that if there was a civil war in China the Communists would probably win, because the Communists were a popular force (9). Why did the American army observers stationed in Yenan call the Chinese Communists the popular force? Were they fooled by the Communists? Or did they see more and knew more about Chinese Communists and Chinese farmers than most other Americans? The Truman Administration did not heed the warning of their diplomats in the fields, and recklessly threw its support behind the unpopular Chiang Kai-shek Government, starting a long tradition of backing unpopular dictators in the third world. At the beginning of the civil war, Chiang Kai-shek, with a much larger and superiorly armed military force, with the generous support of the American Government, appeared to have an upper hand against the Chinese Communists. The Communists were on the retreat, and the Nationalists were on the offensive. Under the nationalist military offensive, the Communists abandoned their capital, Yenan, in March 1947. But just one year later, the tide turned. The Nationalists were on the defensive, and Chiang’s army began to take one beating after another. By mid 1949, Chiang’s fate was sealed, and on October 1, 1949, the People’s Republic of China was founded. Chiang squandered all his political, military and economic superiority, and fled to Taiwan. American investment and American grand schemes about China were completely wasted. Why were the Communists able to beat all the odds to win the civil war?

As soon as the civil war started, the Communists resumed the land reform program in regions under their control, which was suspended because of the second united front against the common enemy Japan. The land reform turned the Chinese civil war between the Chinese communists vs the nationalists into a war between the Chinese poor peasants against the landlords, releasing tremendous revolutionary energy among the seventy percent of Chinese rural population. During the Huaihai Battle in the spring of 1949 the nationalists gathered a much bigger force, 800,000 troops, plus the control of the air space. The communist forces were only 600,000 which were poorly armed in comparison. But during the battle, 5,430,000 Chinese farmers from Jiangsu, Shandong, Anhui and Henan Provinces joined the war on the communist side, nine times bigger than the soldiers involved in the fighting on the communist side. Of these more than five million farmers, 220,000 were in the front supporting the Communist army, 1.3 million were on second line, and 3.91 million were working elsewhere. They utilized 206,000 stretchers, 880,000 carts and wheel barrows, 303,000 shoulder carriers, 767,000 animals and 8539 boats, collecting close to ten million jin of (0.5kg) grain and shipped 4.34 million jin of grain to the front. Why did the Chinese farmers go all out to support the Chinese Communists in the civil war? Their interests were bound with the cause of the Chinese Communists. The poor Chinese peasants, who got their land from the land reform, saw the Chinese Communist Party and its leader Mao Zedong as their savior. It is hard for any Americans to understand the importance of land for the Chinese farmers. It is their life. It is their lifeline (10). If the nationalist won the war, the returning regiments made up the former landlords who lost land during the land reform, would have returned to the villages. The poor farmers would suffer retaliation and revenge by the landlords. The Chinese poor farmers could not afford to allow the nationalists to win the war.

In fact, about one third of Chiang’s army did not fight at all and simply surrendered to the communists during the war. Most of the prisoners of war from the nationalist army joined the Chinese Communist fighting units almost immediately. The nationalist soldiers mostly came from the poor farmers’ families, just like the communist fighters. Most of them were drafted by the landlord controlled local government at gun point. They shared the same hatred against the landlords and rich peasants back home as the communist fighters. It took only one “speaking bitterness” meeting (suku dahui), which was a common practice during the land reform, of which DeMare discussed very extensively in his book, for these former “enemy” soldier to realize that they and the communist fighters share one common enemy: the Chiang Kai-shek government backed by the landlord class (11).

In 1950, UN forces in Korea headed by the U.S. the most powerful military in the world at the time, and fifteen other countries, were advancing toward the Chinese border, chasing the North Korean Army. The newly founded PRC government warned the U.S. that it would not stand idle and watch its neighbor get trampled by foreign military forces. But nobody paid any attention. MacArthur flew to Taiwan to meet with Chiang Kai-shek. He threatened to roll back Chinese communism and reverse the result of the Chinese Civil War. Worried about the prospect of drawing Chinese communists into the conflicts, President Truman flew to meet MacArthur on Wake Island to discuss American strategy in Korea. MacArthur told the concerned president that the best time for the Chinese involvement in Korea was over. If the Chinese dared to get involved, it would be the biggest man-slaughter in human history. The Chinese had been humiliated by the West for over one hundred years, and bullied by the west and Japan repeatedly up to that moment in history. The pathetic truth was that China was never able to beat any invaders on their own soil up until then.

Now faced with the most formidable military group in human history on foreign soil, most Chinese generals and foreign observers did not think that China had any chance in Korea. Mao was the only one among the Chinese top leaders who believed that China should get involved in Korea, and he later convinced Peng Dehuai, one of his most trusted generals, to command the Chinese volunteers in Korea. In a matter of a few weeks, the poorly armed Chinese volunteers, without an air force and without an industrial base to support a large scale war on foreign soil, were able to push the UN forces away from the Chinese borders and all the way back to the 38 parallels. Many military observers believe that the Korea War was a draw between China and the U.S. Even if it was a draw, it was already a big historical victory for the Chinese military, let alone the fact that Chinese volunteers actually pushed the UN forces all the way from their borders back to the 38 parallels, accomplishing its political objectives.

Why could the Chinese volunteers beat the most formidable military group in human history without an air force and a navy? There may have been many factors at play. But it is easy to see that Chinese volunteers were very different from the traditional Chinese military the foreigners knew before. They were a politically charged military. They knew why they were fighting and whom they were fighting for, very different from Chiang Kai-shek’s soldiers and that of American soldiers. This political awareness of Chinese soldiers was directly connected with the land reform, the long term political objective of the Chinese Communist Party and the Chinese soldiers who made up of the Chinese Communist Army. The Chinese volunteers were made up of poor Chinese farmers, whose family just got land from the land reform, knew they were fighting for their land. When MacArthur said that he wanted to reverse the result of the Chinese civil war, he did not know what he was talking about. He was challenging the five hundred millions Chinese farmers who just got their land in the land reform, and who were ready to defend the fruits they got from the land reform with their own lives. In a way, the land reform contributed tremendously to the victory of the Chinese volunteers in Korea.

Before the Chinese Communists came to power and before the land reform, opium addiction was wide spread in China. Prostitution was rampant in Chinese urban areas. Bandits and criminal gangs operated freely in China. There were also poor people referred to by the landlords and gentry class as hooligans ( erliuzi) which was a considerable problem in China. In the eyes of the Chinese gentry class and the Chinese elites, these hooligans were good for nothing people in Chinese society and to be despised. DeMare discussed this issue in his book. But once land reforms were carried out, opium addiction disappeared. Bandits and criminal gangs were completely wiped out, and prostitutes became something of the past in China for about thirty years. Those people who were considered hooligans were able to work hard once they got their own land. Land reform turned China into a much healthier society in many aspects. In 1949, China’s life expectancy was only 32 years, by 1976, when Mao died, Chinese people’s life expectance reached 69 years, more than doubled in less than thirty years. Land reform and collective farming transformed China completely. DeMare and his American colleagues tend to see the land reform in isolation. But nothing in this world exists in isolation. The difference between Mao and his critics is that Mao always kept the inherent connections of social institutions and practices in mind when he designed the land reform policies. Land reform is not just land reform, it gave rise to many things, many of which were good things.

Before the land reform, the poor tenant farmers had no desire to invest in the landlords’ land they were farming. They barely got enough to eat, and could not afford and had no interest to invest in the landlords’ land. The landlords got so much out of the land they leased to the poor farmers, and they did not see any point in investing in the land. Land reform released great productive potential among the poor Chinese farmers and provided them incentive to invest in the land and in the rural infrastructure. In the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s, particularly during the Great Leap Forward, Chinese people turned the traditional idle seasons into building reservoirs and other irrigation projects. They built more than 84,000 reservoirs during the Great Leap Forward, more than the total number China ever built up to that point.

Many American and Western scholars and Chiang Kai-shek supporters tend to argue that the Chinese Communist Party took away the Chinese farmers’ land after the land reform through collective farming. That was simply not true. Collective farming was a management style transformation; the individual household management style was uplifted into a joint venture management style. The farmers pooled their resources together, and they continued to own their land jointly and they never lost the control of their land. Land reform gave the Chinese farmers the permanent ownership of their land. As long as they continue to live in the rural community, they continue to own the land unless they jointly agreed to give up their land. After the collectives were broken up in 1979 by the Chinese government, the Chinese farmers divided up their land equally among themselves. That is why China does not have much a large problem with hunger and homelessness, or even an unemployment problem, today. Every farmer has a home built on his own land, of which he does not need to pay any real property tax, and has a piece of farm land on which they can grow enough food for themselves and their family, of which he does not need to pay any taxes on. When they lost their employment in the urban area, the migrant farmers could always return to their home village to resume farming. Land reform is still providing the foundation for China’s social stability even today.

In order to prove the excessive violence, DeMare quoted Deng Xiaoping: killing more and more people because farmers wanted more to be killed. In the end, forty more percent of the people were killed (P17). What DeMare depicted here was more like the killing of the people by the nationalist forces after they captured the areas controlled by the Communists previously. But the source of this quote was only somebody else’s quote. It does not mention where and when Deng Xiaoping made the speech and where the incident of killing was referring to. In the book, DeMare talked about “Attacks on farmers.” Who were the farmers, the landlords, the rich peasants, or the poor farmers? (p. 18). The land reform was an attack on the landlords and rich peasants by the poor peasants.

DeMare talked about Mao’s dismissive view of the group (intellectual) (p. 34), but he does not provide any proof. When and where did Mao ever dismiss the intellectual group? It was true that Mao disliked the intellectual’s tendency to look down upon the working class, and encouraged the intellectuals of the Chinese Communist Party to integrate with and learn from the working classes during the war time, during the land reform, and during the Cultural Revolution. That was one of the reasons the Chinese Government called on the urban intellectuals to participate in work teams of the land reform. It is a universal tendency for the educated elite to look down upon the working classes, particularly farmers, throughout the world. Because of Mao’s leadership and vision, the Chinese Communist Party and the Chinese government gradually mitigated this tendency among the Chinese intellectuals. The fact that China developed faster than most other third world countries, in a way, vindicated Mao’s effort and vision. Because Chinese intellectuals integrated more with Chinese working classes in response to Mao’s call and encouragement, China has a smaller divide between the urban and rural, intellectual and working class in its society, unlike the divide between the blue and red states in the U.S. and yellow vest protests in France. Qian Xuesen, the US trained scientist, who returned to China in 1955 despite American efforts to block his return, was so excited when he learned that he was nominated together with Lei Feng, Jiao Yulu, Wang Jinxi and Xi Laihe as the representatives of the most respected people in China. For him, it was a great honor to be considered a member of the working class (12).

DeMare documents many and various errors that occurred during the land reform in different regions and different times, and who were responsible for these errors. In a way, it is important to know these errors, which the Chinese Communist Party itself admitted and documented these errors and deviations during the land reform. The land reform was an unprecedented revolution in human history. There was no clear path ahead. It was a trial and error effort. The Communist Party leadership and the Communist Party functionaries were baptized and trained and become better through this trial and error process. It was a learning process for the party and party functionaries. The hundreds and thousands of inexperienced young urban intellectual who went through the storm of land reform were tempered and transformed through the revolutionary practices and struggles on the ground. They became the most important assets of the Chinese nation and the Chinese people. Mao was responsible for the mistakes of the Chinese revolution, but in the same token, the credit of the success of the Chinese revolution and Chinese nation should also go to him as well.

DeMare also paid significant attention to many and various rumors during the land reform time. These rumors were mostly created and spread by the landlords and nationalist government to scare and intimidate the poor peasants in order to prevent the land reform. But rumors and propaganda were a doubled edge sword. If the rumors were proven true, then it would accomplish the political objectives of those who created and spread the rumors. But if the rumors were proven to be wrong, it not only failed to accomplish the intentions of the rumor, but also destroyed the credibility of those who created and spread the rumors. When I was doing research in Shandong Province, many farmers told me that before the PLA came to their region, the landlords who fled from the liberated areas told them that the communist party was bandits and criminal gangs. They would take away everybody’s land, property, and wife to share with others. At the beginning, they tended to believe these rumors. But when the communist party and PLA came, and treated the poor farmers nicely, and fairly, they began to see why the landlords created and spread rumors like what they did. They learned something. They began to see why bad things for the landlords could be a good thing for the poor farmers.

Land reform also transformed everybody who had gone through it. The poor villagers, more prosperous villagers, rich farmers and landlords, the village cadres and work team members, were all impacted by the experience of the land reform in their own way. That is the significance of the land reform. Chinese people and Chinese society were modernized through political meetings after meetings. Chinese villagers might be fearful of outsiders (p 57) before land reform, but they were no longer fearful of outsiders after interacting with the work team and getting to know them intimately. The Chinese Communist Party earned the poor people’s trust through its hard work to mobilize the poor majority of the Chinese rural society. No other political party in human history ever devoted such a large scale effort and enthusiasm to mobilize the people. Land reform tempered a large number of Communist Party functionaries. They became a more down to earth, more disciplined group than before the land reform. The communist party accumulated great assets and skills in mobilizing and organizing people through the land reform as a social movement.

DeMare talked about the emancipation of woman merely as a gender issue (p 62-63). His discussion of women speaking bitterness and crying while they were speaking as if women were more inclined to cry, and their tears were utilized by the Communists to mobilize for the land reform. He did not discuss why these women cried, and why the audience resonated with their stories of bitterness. He did not appreciate how powerful an impact land reform had on women. Women got land, got the opportunities to speak at the mass meetings in the villages. Women joined village militia, and organized women federations. To a large extent, women gained equality in China politically and economically starting with the land reform.

DeMare admitted that Ding Ling’s work was immensely influential, while Zhang Ailing’s Love in Redland had little impact, forgotten. (p 30) Ding Ling’s work resonated with Chinese people’s experience during the land reform. Zhang Ailing’s Love in Redland was forgotten because it fails to reflect the reality of the land reform. Like Zhang Ailing’s Love in Redland, DeMare’s work and many of other China scholars’ scholarship will not have much impact on Chinese people’s perception and understanding of the land reform, but will only serve to cement the existing bias and misunderstanding of Chinese land reform, Chinese Revolution, Great Leap Forward and Chinese Cultural Revolution existing among American public already. But what American people need to know is how the land reform provided the foundation for the success of the PRC and its rise in the world today.

References:

1- Edward Friedman, Paul Pickowicz, Mark Selden, Chinese Village, Socialist State, New Heaven: Yale University Press, 1993.

2- Mao Zedong,” Hunan Nongmin Yundong Kaocha baogao,” (Report on the investigation of Hunan nongmin yundong,” March, 1927.

3- Ding Ling, Taiyang Zhaozai Sangganhe Shang, (The Sun Shines on Sanggan River) Beijing: Remin Wenxue chubanshe, 2001.

4- James Scott, Seeing Like A State, New Haven: Yale University Press, 1998

5- Mao Zedong,” Hunan Nongmin Yundong Kaocha baogao,” (Report on the investigation of Hunan nongmin yundong,” March, 1927.

6– Ding Ling, Taiyang Zhaozai Sangganhe Shang, (The Sun Shines on Sanggan River) Beijing: Remin Wenxue chubanshe, 2001.

7– Zhang Ailing, Chidi Zhilian (Love in the Redland), Taibei:Huangguan wenhua chubanshe, 2003.

8- William Hinton, Fanshen, A Documentary of Revolution in a Chinese Village. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997.

9– Carolle J. Carter, Mission to Yenan: American Liaison With Chinese Communists, 1944-1947. The University of Kentucky Press, 2015.

10- A Meng “yunchou tugai shunmingxin, juesheng zhanchang chu jianghuo” (implementing the land reform to fulfil people’s desire, and eliminating the Jiang Jieshi on the battle ground) http://www.cg.cn August, 2019.

11- Zhang Ying, “guojun fulu wei he xunsu biansheng wei ‘gongchanzhuyi zhanshi,’” (Why the prisoners of nationalist army quickly became communist fighters”, zhonghuawang, November 10, 2011.

12- Wang Jianzhu, “Qian Xuesen: cisheng weiyuan chang baoguo—woshi laodong renmin yifenzi” (Qian Xuesen: It is my life long wish to serve the state and people—I am a member of working classes) www.people.com April 15, 2008.

###

Do your friends, family and colleagues a favor to make sure they are Sino-smart:

PRESS, TV and RADIO

About me: https://chinarising.puntopress.com/about-the-author/

Bitchute videos: https://www.bitchute.com/channel/REzt6xmcmCX1/

Books: https://chinarising.puntopress.com/2018/06/18/praise-for-the-china-trilogy-the-votes-are-in-it-r-o-c-k-s-what-are-you-waiting-for/

Brighteon videos: https://www.brighteon.com/channels/jeffjbrown

iTunes: https://itunes.apple.com/cn/podcast/44-days-radio-sinoland/id1018764065?l=en

Ivoox: https://us.ivoox.com/es/podcast-44-days-radio-sinoland_sq_f1235539_1.html

Journalism: https://chinarising.puntopress.com/blog-2/

Odesee videos: pending review

RUvid: https://ruvid.net/w/radio+sinoland

Sound Cloud: https://soundcloud.com/44-days

Stitcher Radio: http://www.stitcher.com/podcast/44-days-publishing-jeff-j-brown/radio-sinoland?refid=stpr

YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCS4h04KASXUQdMLQObRSCNA

Vurbl audio: https://vurbl.com/station/1Vc6XpwEWbe/

Websites: http://www.chinarising.puntopress.com ; www.bioweapontruth.com ; www.chinatechnewsflash.com

SOCIAL MEDIA

Email: je**@br***********.com

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/44DaysPublishing

Flickr: https://www.flickr.com/photos/98158626@N07/

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/jeffjbrown_44days/

Line App/Phone/Signal/Telegram/WhatsApp: +33-6-12458821

Linkedin: https://cn.linkedin.com/in/jeff-j-brown-0517477

Pinterest: https://www.pinterest.com/jeffjb/

Parler: https://parler.com/profile/jeffjbrown

Sinaweibo: http://weibo.com/u/5859194018

Skype: live:.cid.de32643991a81e13

Tumblr: http://jjbzaibeijing.tumblr.com/

Twitter: https://twitter.com/44_Days

VK: http://vk.com/chinarisingradiosinoland

WeChat: +86-19806711824

Why and How China works: With a Mirror to Our Own History

JEFF J. BROWN, Editor, China Rising, and Senior Editor & China Correspondent, Dispatch from Beijing, The Greanville Post

Jeff J. Brown is a geopolitical analyst, journalist, lecturer and the author of The China Trilogy. It consists of 44 Days Backpacking in China – The Middle Kingdom in the 21st Century, with the United States, Europe and the Fate of the World in Its Looking Glass (2013); Punto Press released China Rising – Capitalist Roads, Socialist Destinations (2016); and BIG Red Book on China (2020). As well, he published a textbook, Doctor WriteRead’s Treasure Trove to Great English (2015). Jeff is a Senior Editor & China Correspondent for The Greanville Post, where he keeps a column, Dispatch from Beijing and is a Global Opinion Leader at 21st Century. He also writes a column for The Saker, called the Moscow-Beijing Express. Jeff writes, interviews and podcasts on his own program, China Rising Radio Sinoland, which is also available on YouTube, Stitcher Radio, iTunes, Ivoox and RUvid. Guests have included Ramsey Clark, James Bradley, Moti Nissani, Godfree Roberts, Hiroyuki Hamada, The Saker and many others. [/su_spoiler]

Jeff can be reached at China Rising, je**@br***********.com, Facebook, Twitter, Wechat (Jeff_Brown-44_Days) and Whatsapp: +86-13823544196.

Read it in your language • Lealo en su idioma • Lisez-le dans votre langue • Lies es in deniner Sprache • Прочитайте это на вашем языке • 用你的语言阅读

[google-translator]

Wechat group: search the phone number +8619806711824 or my ID, Mr_Professor_Brown, friend request and ask Jeff to join the China Rising Radio Sinoland Wechat group. He will add you as a member, so you can join in the ongoing discussion.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: RSS

I contribute to

I contribute to