NOW IN 22 DIFFERENT LANGUAGES. CLICK ON THE LOWER LEFT HAND CORNER “TRANSLATE” TAB TO FIND YOURS!

By Jeff J. Brown

Pictured above: this massive social statement greets you at the entrance of “Digging a Hole in China”. Behind the pyramid of “Square” is the rebellious “Liao Yuan”, with photographs and a video of all the artist’s illegal construction, including his wacky and whimsical museum, on the back right. (Image by Jeff J. Brown)

Thousands of dollars are needed every year to pay for expensive anti-hacking systems, controls and monitoring. This website has to defend itself from tens of expert hack attacks every day! It’s never ending. So, please help keep the truth from being censored and contribute to the cause.

Paypal to je**@br***********.com. Thank you.

Do your friends, family and colleagues a favor to make sure they are Sino-smart:

Journalism: https://chinarising.puntopress.com/blog-2/

Books: http://chinarising.puntopress.com/2017/05/19/the-china-trilogy/ and

https://chinarising.puntopress.com/2018/06/18/praise-for-the-china-trilogy-the-votes-are-in-it-r-o-c-k-s-what-are-you-waiting-for/

Website: www.chinarising.puntopress.com

Twitter: https://twitter.com/44_Days

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/44DaysPublishing

VK: https://vk.com/chinarisingradiosinoland

Mobile phone app: http://apps.monk.ee/tyrion

About me: https://chinarising.puntopress.com/about-the-author/

Sixteen years with the people on the streets of China, Jeff

For my upcoming book, China Is Communist, Dammit! – Dawn of the Red Dynasty (Badak Merah, summer 2016), I did extensive research on China’s illustrious revolutionary art movement, past and present. My detailed expositions are well juxtaposed with Andre Vltchek, in his 2013 article,

Western Art Is Barking at China, http://www.counterpunch.org/2013/02/15/western-art-is-barking-at-china/, which looks at currents art trends in Beijing and Shanghai. But what about the South of China, in workaholic, frenetic Guangdong Province (Canton), just across the border from the former drug trading capital of the colonial West, Hong Kong?

For millennia, Shenzhen was a sleepy fishing village, surrounded by rice paddies ant dotted with vegetable gardens. Thanks to President Xi Jinping’s father, Xi Zhongxun, starting in 1978, he led turning Hong Kong’s northern neighbor into the global technology cum manufacturing juggernaut that it is today. It is also one of China’s three richest cities, along with Beijing and Shanghai. Given its well-deserved reputation for fast paced, go-go entrepreneurship, Shenzhen would seem an unlikely place for revolutionary, communist art. But, such is China’s surprising, boundary breaking ambitions, what the current administration is calling the “new normal”.

By the standards of Beijing’s 798 and Shanghai’s Art Districts, Shenzhen’s OCAT, or “The Loft”, is a modest affair. In fact, it is more dedicated to hip-chic eateries, local lore coffee roasters and high end interior decoration and clothing. For example, there is an uber snobbish clothing store called “Opium Pipe” (in Chinese, not in English), and on the front door, it flaunts, “Please don’t come in unless invited”. OK, if you insist – while glorifying China’s century of humiliation. I pretty sure I’d have passed anyway.

However, there is one large public, no-charge gallery that turns all this tony ambiance on its materialistic head. Its two garage door sized entrances are not a problem in subtropical Shenzhen, which sits just south of the Tropic of Cancer. Even being the first of April, the clammy steaminess of summer was already being felt in the afternoons. Right inside the entrance is a large wall, featuring a synopsis of the current exhibit, in Chinese and English, with a list of all the contributing artists. The exhibition’s titles in Chinese and English could not be much different. In English, it is “Digging a Hole in China” and in Chinese, it would be translated simply as “Landscape Incidents”.

The synopsis immediately makes it clear that “Digging a Hole in China” is not going to be your run of the mill, commercial eye-candy zone, like so many modern Western exhibitions are and have been for the last 30 years or so. Neil Postman wrote in “Amusing Ourselves to Death”, that the West is not so much Orwellian, but Huxleyan, in the way the elites control and brainwash the people with vacuous entertainment, based on the premise of “A Brave New World”. Englishman Roger Waters lyrically expounded upon this theme in his music album “Amused to Death”. American Edward Bernays wrote the playbook bible on the one-percent controlling the masses, in his chilling book “Propaganda”.

No, much of the Chinese art scene is different and expresses itself with a purpose, to challenge conventional thinking, accepted governmental norms and social propriety. It is for this reason that communist China has much more freedom of creation in the art world, because revolutionary expression has had and continues to possess a proud tradition of defiance in post-1949, liberated New China. This was seen in Jiang Qing, Mao Zedong’s wife, who aspired to radically transform the Chinese people’s views of citizenship, using the stage to do so, with mixed and infamous results. As I show in three collections of art in China Is Communist, Dammit!, this proud tradition of defiance and rebellion has been a seamless timeline into the present, and Digging a Hole in China simply confirms this.

This Shenzhen exhibition states quite clearly that it wants to challenge the West’s “Land Art” movement, which had a popular run starting in the 1960s. The concept was to go “nowhere”, where there were no people, no civilization, and using only natural earth forms and objects to create artworks. Land Art was imported into China in the 1980s and developed its own genre, with Chinese characteristics, as stated in the synopsis,

Produced at different points in time, from 1994 onward, the works in “Digging a Hole in China” delineate the hidden trajectory of land’s conceptual evolution. This strand of art does not attack established systems in a belligerent and explicit manner, but instead subtly exposed the epistemological framework of land, in order to open up new sites beyond it.

While “traditional” Western land art seeks a conceptual and geographical nowhere, the works in “Digging a Hole in China” turn to a variety of issues, such as the rights of ownership, management and land use, and the transfer of and restrictions on these rights, weaving together a massive network that has already exceeded “land”.

I ask you, outside of minority and oppressed groups, when was the last time you saw an art exhibition raise itself to such a lofty vision as this, in Eurangloland? In the West, if it cannot be monetized, like everything else, it loses its purpose.

Chinese land art turns its Western counterpart on its head. Whereas imperial land art intentionally excludes civilization, these Chinese artists revel in humanity and how people and land interact. Even in several of the exhibitions that do not expressly portray the human race, the artists include multimedia – film and sound recordings, to amplify the human aspect and its association to the land in question.

1) Since the 1980s, the city of Dongguan has been one of the manufacturing workhorses in Guangdong Province. Guangdong represents about one-third of China’s manufacturing capacity and Dongguan has been its heart and soul, along with Shenzhen. Shenzhen has not missed a beat, as it has deftly transitioned from OEM (Original Equipment Manufacturer), low value factories, to high value, high tech production, backed by ample research and development (R&D). Dongguan was not so fleet footed and by 2012, only had 1-2% GDP growth. It rapidly became the poster child of China’s OEM industrial past: thousands of shuttered factories, drugs, prostitution and money laundering. In the national media, Dongguan was branded as China’s bad boy, and a model to avoid. The city’s Party chief, Xu Jianhua and his administration took all the body blows in the press, while asking for everyone’s patience to turn things arounds. With China’s miraculous communist central planning, Dongguan has rebounded, with 986 innovative enterprises and 28 research organizations, leading this once beleaguered city to 8% growth in 2015. Per capita GDP is back up over $12,000 and Dongguan is again giving its sister city, Shenzhen, a serious run for the money.

Artist Li Jinghu (b. 1972, Dongguan; graduated from the Fine Arts Department, South China Normal University), managed to get his hands on the marble flagstones of Dongguan’s central plaza and cut them into various shapes, to create a big, solid pyramid. In “Square” (2016), Li explains that he wants to question his hometown’s plaza as an architectural form and as a symbol of authority. Mao Zedong would have approved, wholeheartedly, and would probably have written a darn good poem about it.

Li Jinghu’s “Square” pyramid, back right, greets you, as you enter the exhibition. In the foreground is the comprehensive “Liao Yuan”. Straight back are the two video screens of the “Zhuang Hui Solo Exhibition, with the photo of his giant blue sculpture he left in the Gobi Desert. To the back right is the video “Upstream”. (Photo by Jeff J. Brown)

2) Zhuang Hui (b. 1963, Yumen, Gansu) offers two works of land art for “Digging”. Yumen figures in my book, “44 Days”, https://ganxy.com/i/88276/jeff-j-brown/44-days-backpacking-in-china-the-middle-kingdom-in-the-21st-century-with-the-united-states-europe-and-the-fate-of-the-world-in-its-looking-glass as it is home to one of the oldest forts along the Great Wall, along the Silk Road, going back to the Han Dynasty, over 2,100 years ago. It was here, for millennia, that the Chinese protected the west end of the celebrated Hexi corridor, that hugs the majestic Qilian Mountains, as travelers and merchants wended their way to and from Lanzhou, now Gansu Province’s capital city. As a child of the desert, Zhuang sees sublime beauty and feels a profound sense of spirituality, in what most urbanites would call the wastelands of the vast Gobi plain. In “Zhuang Hui Solo Exhibition” (2014-), he juxtaposes two cameras filming his trek across his beloved desert, with a fellow companion, on foot and in a vehicle, so we see and hear his adventure simultaneously, from different angles. While transporting and leaving a massive sculpture for posterity, on the China-Mongolia border, he says that “A Nietzschean retreat to the desert is a ‘deliberate obscurity’, a ‘getting out of the way of one’s self’, to a ‘nowhere’, that is at once intrinsic and extrinsic to humanity”. Instead of excluding Homo sapiens from Western land art, Zhuang wants to suck our beating hearts into the Chinese desert’s deepest, most naked soul. As a passionate desert lover and traveler, I can fully relate to his vision.

In two videos, Zhuang Hui walks, drives and talks with his desert rat buddy about what the Gobi means to him spiritually. They left a huge sculpture in perpetuity, along the China-Mongolia border. (Image by Jeff J. Brown)

3) Zhuang’s second work presented is truly political dynamite. Entitled “Longitude 109.88°E 31.09°N (1995-2008), he dug a number of holes along the Changjiang River (Yangtze), where the Goliathan Three Gorges Dam project would eventually fill up, along with thousands of villages and cultural sites. “Longitude” shows a large topographical map of the Three Gorges flood zone and Zhuang marks all the places along its length, including three villages he visited, and where he dug his holes. He recorded his and the villagers’ thoughts, which visitors can listen to. They expound on the world’s largest reservoir project and the power of the human race to so permanently transform Earth, that we are now said to be living in the Anthropocene Era. While Three Gorges was and is relentlessly lambasted by Westerners, Baba Beijing went to extraordinary lengths to make sure that the area’s 1.24 million residents, 13 cities, 140 towns, 1,350 villages and 1,300 cultural sites were all moved, with as little shock to those involved, as possible. In fact, an unbelievable 54% of the entire dam project went to taking care of these people and their cultural heritage. That would never happen in the capitalist West. Even in China, it was an explosive topic, given the magnitude of the transformation and societal disruption. A massive and ongoing education media campaign defused much of the nation’s angst. Zhuang’s subtle, yet daring exhibition really captures the people’s zeitgeist.

“Longitude” shows photographs of all the holes that artist Zhuang Hui dug along the flood zone of the Three Gorges Dam project. On the right is the big satellite map marking each of these spots, as well as the three villages he visited. Three recording and videos of the artist’s and villagers’ thoughts are on offer. To the front left is the tail end of “Propitiation”. (Photo by Jeff J. Brown)

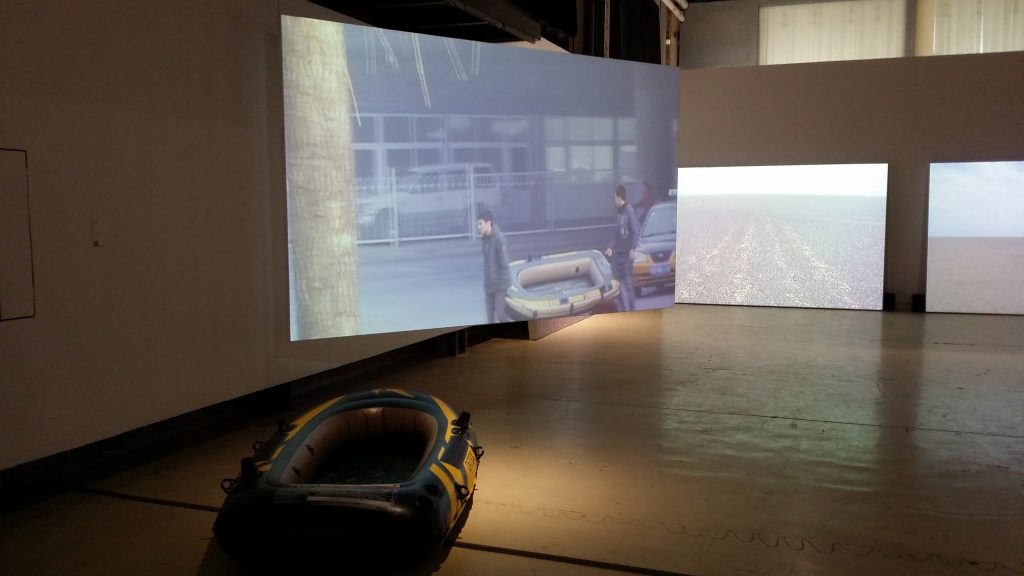

4) In “Upstream” (2011), Xu Qu (b. 1978, Jiangsu; MFA in painting and film from Braunschweig University of Art, Germany) films himself and a buddy with a three-meter long rubber dingy, trekking into Beijing. Starting out rowing in a fetid creek on its outskirts, they keep moving inward, carrying their mode of transportation on foot, until coming upon the next body of water, only to row in it, until it has been crossed. Some of them are only puddles big enough to fit the dingy in, so they act out a sort of “veni, vidi, vici”, “I came, I saw, I conquered” shtick, giving the artwork a certain, absurd, comic appeal. After traipsing across Beijing land and water for five hours and making it all the way downtown, they were finally stopped by the police and asked to stop. Xu’s vision is to show that there is an inverse relation between urbanization and beautiful scenery, and that there is an inevitable stratification in both city landscapes and social structure. Deep thinking, for sure.

The idealistic video “Upstream” and the rubber dingy that the artist used to create his work. Like a number of these land artworks, breaking the law and challenging government authority figure prominently as a theme. Mao Zedong would not have wanted it any other way. (Photo by Jeff J. Brown)

5) “Liaoyuan” (meaning “Accomplished Garden”) was originally named “Age of the Empire” (2004-). It was created by Zheng Guogu (b. 1970, Guangdong; graduated from the Department of Printmaking at the Guangzhou Academy of Fine Arts). Zheng purchased four hectares of land in his hometown of Yangjiang, to create his own empire: roads, flora, building a museum, while moving around tons of rocks and dirt, and intentionally violating many building codes in the process. Considering it his social network and a way to find his muse, he has endured endless negotiations with the local authorities and paid numerous fines. For Shenzhen, he brought a special hanging funnel to the exhibit, and dropped two truckloads of his garden’s soil through it, to create dirt pyramids on the exhibition floor, harking to the power of authority expressed in the aforementioned “Square” exhibit (#1), by Li Jinghu. Zheng also displays a number of photos of his rebel garden, including the wacky and whimsical exterior of his museum. Whoever says communist China is a rigid, authoritarian society is wearing Western propaganda blinders and doesn’t see the half of it.

The socially rebellious, law breaking expression of land art, by Zheng Guogu, in “Liao Yuan”, complete with pyramid shaped piles of soil from his huge garden. Behind it to the left is “Propitiation”. (Image by Jeff J. Brown)

6) Artist Zheng was able to offer another land art work, with a 1994 filming of “Planting Geese”. Again in his hometown, he and a bunch of friends drew a huge pentagram on the construction site of sugar factory. They then plotted out and marked their “farm”, carefully planted geese in the soil, painted their heads with ink, then gently unearthed them and released them. This 47-minute filmed performance definitely delves into the theater of the absurd, while challenging every notion of what land use is and should be.

The absurd notion of “Planting Geese”, on the construction site for sugar mill, while questioning how land should really be used. (Photo by Jeff J. Brown)

7) Xu Tan (b. 1957, Wuhan; got his MFA from the Guangzhou Academy of Art) takes on Western empire with a stiletto vengeance, in his exhibit “Land and Turf” (2016). As someone who is three years older than Xu, I can empathize with him that we often don’t see the bitter truth about Western racism and colonialism, until being much older. Using seven video screens running simultaneously and randomly, he offers a table, two chairs and a couple of tablets for visitors to collect their thoughts, as well as a scarecrow to hang small notes of comments. Next to the message laden scarecrow is a Latin law posted on the display wall,

Cuius est solum eius est usque ad coelum et ad inferos (Whoever’s is the soil, it is theirs all the way to heaven and all the way to hell”).

Which reminds us that land ownership and its use go back to the dawn of sedentary civilization, for better and for worse.

Three of the screens show how the people of Lijiao, Guangzhou, have kept their community intact, after being dispossessed of their ancestral lands on shore, for a modern development project. A water dwelling people, they have built little floating islands to grow their food and tend to them from their boats. Like “Longitude” (#3), headphones are provided, so we can hear the trials and tribulations of Chinese citizens who have been victimized by “progress”. Talk about land art with a social conscious.

The seven video screens, table to sit for reflecting and the scarecrow to hang a well thought out message, in the anti-imperialist, anti-colonialist, anti-West, anti-Zionist “Land and Turf”. (Photo by Jeff J. Brown)

The other four screens are a big loop of slides, repeated over and over. One series is in normal color. A second presents the same images in photo negative, giving the images a shocking, haunting feel. The third series is in 19th century daguerreotype colors, rendering the collection with its deep historical context. The images are based on the legal tome “Oppenheim’s International Law – Volume 1 – Peace” (OIL). The subtitle “Peace” is a chilling reminder of Orwellian doublespeak. Just ask humanity’s 85% non-Caucasian peoples. Xu flashes excerpts from OIL, along with his own comments (in bold below) and other visual media. The effect is brilliant and mesmerizing, as it chilling spells out in pathological and Machiavellian terms, Western empire, with its genocidal vortex of racism, capitalism and colonialism. More importantly, it shows how the White race continues to justify its exploitation of the world’s natural resources and the extermination of humanity’s dark skinned peoples. To wit,

“The fact of occupation forms the basis of rights of ownership”. – Vol. 1 of OIL

“Possession and administration are the two essential facts that constitute an effective occupation”. – Vol. 1 of OIL

“In 1823, England occupied, in consequence of a so-called cession from native chiefs, a piece of territory at Dologoo Bay, which Portugal claimed as part of her territory owned at the bay, maintaining that the chiefs concerned were rebels”. – Vol. 1 of OIL

The Western bible of racism, capitalism, imperialism, colonialism and war: Oppenheim’s International Law (Photo by Jeff J. Brown)

People give proof of ownership only on the basis of the fact of occupation, instead of using logical ways. On the other hand, they attempt to use strict, logical ways to make and exercise the law after occupation.

“Five modes of acquiring territory have traditionally been distinguished, namely: cession, occupation, accretion, subjugation and prescription”. – Vol. 1 of OIL

“Article 52 of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, “A treaty is void if its conclusion has been procured by the threat or use of force, in violation of the principles of international law embodied in the Charter of the United Nations”. – Vol. 1 of OIL

Who has the right to possess Jerusalem?

A timeline shown in “Land and Turf”, chronicling Anglo-Zionism’s genocide in Palestine, and this people’s heroic resistance to being exterminated. (Photo by Jeff J. Brown)

“Occupation is the act of appropriation by a state in which it intentionally acquires sovereignty over such territory, as is at the time it was not under sovereignty of another state”. – Vol. 1 of OIL

“To do more than note this problem would be to enter upon larger questions of lawful and unlawful use of threat or force, and open the scope of the limits of self-defense”. – Vol. 1 of OIL

Who has the right to possess Sarajevo?

“The only territory which can be the object of occupation is that which does not already belong to any state, whether it is inhabited or uninhabited by any persons whose community is not considered to be a state”. – Vol. 1 of OIL

“Cession of state territory is the transfer of sovereignty of a state territory by the owner-state to another state. History presents innumerable examples of such transfers of sovereignty”. – Vol. 1 of OIL

The surreal photo of a Native American powwow, while flying the flag of their oppressors. (Photo by Jeff J. Brown)

Who has the right to possess T…?

“There has always been some opposition to prescription as a mode of acquiring territory. Grotius rejected the usucaption of Roman law, yet adopted from the same law immemorial prescription for the law of nations”. – Vol. 1 of OIL

Whatever differences there may have been among jurists, the state practice of the relevant period indicates that territories inhabited by tribes or peoples having a social and political organization, were not regarded as terra nullius. – Western Sabara Case, International Court of Justice (1975, Page 39)

If existence cannot be without law, art cannot be without logic.

“In international practice, a state has been considered to be the lawful owner, even of those parts of its territory of which it originally took possession wrongfully, provided that the possessor has been in undisturbed possession for so long, as to create the general conviction that the present condition is in conformity of international order”. – Vol. 1 of OIL

“Whilst not requiring possession from time immemorial, it is held that undisturbed, continuous possession could, under certain conditions, produce a title for the possessor, if the possession has lasted for some length of time”. – Vol. 1 of OIL

How to prove that conquering land is legal?

“The territory must really be taken into possession by the occupying state”. – Vol. 1 of OIL

“Subjugation, that is the acquisition of territory by conquest followed by annexation, and often called title by conquest, had to be accepted into the scheme of modes of acquisition of title to territorial sovereignty, in the period when the making of war was recognized as a sovereign right, and war was not illegal”. – Vol. 1 of OIL

How to prove that conquering land is illegal?

“Yet, not every use of force is unlawful, and a problem remains concerning the possible consequences of the unlawful use of force, or threat of force, notably the inherent right of individual or collective self-defense, if an armed attack occurs against a member of the United Nations, provided for in Article 51 of the Charter of the United Nations”. – Vol. 1 of OIL

In addition to this breathtaking, awe inspiring collection of thought provoking quotes, artist Xu Tan intersperses them with a timeline of Zionism’s genocidal expansion in Palestine, since 1947, satellite images of the Jordan River and Sea of Galilee; maps of ancient Mayan lands; Native Americans having a big powwow, with American flags hoisted in the crowd; a classic photo of a female peasant PLA fighter, with her old carbine hanging on her shoulder; a photo of a parade of Tibetans, marching below the Jokhang Temple, in Lhasa, while hoisting Chinese flags, along with a photo showing PLA troops marching into Tibet. To top it off, Mr. Xu included in Chinese, quotes by William Wordsworth, Franz Kafka, Samuel Beckett, Percy Bysshe Shelley, Leo Tolstoy, John Keats, Friedrich Nietzsche, Euripides and Allen Ginsburg. Now, stuff all that into your cranium, mull it over and leave a note or two on your own scarecrow!

Safe to say, that in the West, “Land and Turf” would never see the light of day, as Anglozionism is getting countries like France, Germany and Britain, to pass laws making it a crime to criticize the state of Israel. Xu Tan would probably go to jail for trying to show this artwork in the “free” West. In communist China, he is free to communicate with the public.

8) Artist Zhang Liaoyuan (b. 1980, Weifang, Shandong; graduated from the China Academy of Arts), Filming a documentary and presenting collected documentation, it challenges authority and the notions of ownership with his simple and elegant “1m2” (2006). In the middle of one of Hangzhou’s busiest intersections, he dug up one-square meter of the concrete street, all 50 centimeters of its thickness, and then waited to see what would happen. Then next day, the street was repaired by the city. Enough said.

9) “Propitiation” (2007, 2016) is a team effort. The two artists are Liu Wei (b. 1972, Beijing; graduated from the Department of Oil Painting, China Academy of Art) and Colin Siyuan Chinnery (b. 1971, Edinburgh). Propitiation refers to the Taoist ritual of giving thanks to the God of Land. It is composed of two parts. One is a massive cinder block building adorned with green and white geometric shapes, that can be looked at and into, via different portals, evoking a collage of different perspectives on space and land. The second part is even more audacious and we have OCAT to thank, for allowing Liu and Chinnery to literally jackhammer deep holes into the exhibition floor, in the shape of a dozen common symbols, in which the middle of, they laid down an asphalt path! This all evokes the daunting images of urbanization: excavation, construction, paving and traffic. Here’s to the God of Land.

The hugely ambitious “Propitiation”, with a look-in room of dazzling geometry, an asphalt road and amazingly, deep pits jack hammered into the exhibition floor, thanks to the good graces of OCAT. (Photo by Jeff J. Brown)

10) Urbanization in China has brought the modern scourge of heavy traffic on overcrowded streets and expressways, and with it, the use and rights of driving space. Liu Chuang (b. 1971, Hubei; graduated from the Hubei Academy of Fine Arts) juxtaposes this sense of land use alongside respect for law and order, with his “Untitled (Dancing Partner)” (2010). In this five-minute video, Liu filmed two identical, working class cars driving side by side at the legal, posted speed limit, on the aggressive, mean streets of Beijing. The results are fascinating. Liu wants to expose the hegemonic majority of drivers forcing its own set of rules on the law abiding minority. He also wishes to highlight these laws as an expression of institutionalized power, rendering two mutually exclusive frameworks that do not overlap. For me, driving in China’s cities will never be the same.

An original look at the law of the jungle, the jungle of Beijing’s mean streets, that is, in “Untitled (Dancing Partner). (Photo by Jeff J. Brown)

11) Meriting accolades from Frederico Fellini, “Rumba II: Nomad” (2015), by Cao Fei (b. 1978, Guangzhou, got her BFA from the Department of Decorative Arts and Design at the Guangdong Academy of Fine Arts), turns the reality of a demolished Beijing neighborhood, into a surreal landscape. Cao’s film shows robot vacuum cleaners, topped with stuffed, egg laying chickens, trying to clean up piles of rubble and debris, while a peasant, adorned with a flower filled straw hat and looking like a lost Pancho Villa, walks in and around the destruction, while blowing on a saxophone. For those of us used to seeing these razed sites around the suburbs of Beijing, this is all abstract food for thought.

The Fellini-esque “Rumba II: Nomad”. There are many of these razed sites in Beijing, frozen in time, until a burst of construction transforms them. (Photo by Jeff J. Brown)

12) Thomas the Tank goes China in Cao Fei’s second presented film work, “East Wind” (2011-2015). She decorated a blue East Wind brand transport truck, to look like this beloved animated and book character. Thomas the Tank East Wind goes about its normal daily routines, loading up and delivering materials around Beijing, filling up with fuel, where it finally ends up in a junkyard. Cityscapes and the reactions of passersby are recorded, including a hilarious stop by a traffic cop, telling Thomas’ driver that the truck is illegal and to get off the road, again questioning the appropriate use of authority, as is the case throughout this exhibition.

Thomas the Tank never had it so good, than in the humorous and thought provoking “East Wind”. Here, he cannot leave the gas station, without all the attendants insisting they have a photo with him. (Photo by Jeff J. Brown)

13) More challenges to the government’s reach and notions of land ownership are on display in the film “Living Elsewhere” (1999), by Wang Jianwei (b. 1958, Sichuan; MFA from the Department of Oil Painting at the Zhejiang Academy of Art). This moving, 40-minute movie shows four farmers, from different parts of China, who have lost their land to urban and industrial development. They converge on a luxury villa project gone bankrupt, near Chengdu’s airport, the capital of Sichuan. These ghostly villas have been abandoned for seven years and are empty shells, sticking up out of overgrown land. These four now landless farmers, thrown together by fate, live in the abandoned villas, scrap together some tools and seeds, and start growing vegetables and crops again. They talk to the cameraman about their travails, their once shattered dreams, the hard times they are living and their hopes for reviving a new future in Villa Land. This is an extremely deep and meaningful piece of land art, after 30 years of breakneck development across China, the good, the bad and the ugly.

Toting a baby and eking out a subsistence existence, at an abandoned luxury villa project, in “Living Elsewhere”. (Photo by Jeff J. Brown)

14) Artist Wang has a second exhibit, a one-hour film called “Production” (1996). He uses the tables inside one of Sichuan’s celebrated tea houses, as a metaphor for different lands. Wang films the people talking, telling stories, gossiping and drinking their leaf infusions. As the customers move around, each table symbolizes land that the imbibers can only access on the periphery, and Wang asks us to think how each table is separate and how everyone intersects through discourse.

The eerie, symbolic people and lands in the tea house of “Production”. (Photo by Jeff J. Brown)

15) Wang was honored with a third photo exhibit, called “Circulation: Sowing and Harvesting” (1993-1994). He returned to the village where he lived during the Cultural Revolution, as a city slicker urban youth, to be reeducated by the peasants. Wang brought back advanced hybrid wheat seed, which the farmers planted and harvested. They signed a contract together and the harvest not only satisfied the village’s allotment sold to the government grain stores, Wang came home with 50kg of wheat to mill and make flour. Wang is not the only urban youth going back to seek inspiration from their days toiling in the fields, 1969-1976. China’s President Xi Jinping has returned several times to his village in Shaanxi Province, and cites his years there as a foundational life experience, which helped make him the man he is today.

16) Lin Yilin (b. 1964, Guangzhou; graduated from the Department of Sculpture at the Guangzhou Academy of Fine Arts) built a three-meter tall and twelve-meter long wall alongside a lake and made a film about it, called “Whose Land? Whose Art” (2010). This is probably the most esoteric work in the exhibition. Lin installed an ancient Chinese scale in the wall and weighed all the participants with it, then wrote their names and weights on the façade. Thereafter, all the visitors sat atop the wall, fishing with poles and admiring the surroundings. At 50 minutes, I did not have time to watch and listen to the whole film, and thus surely lost much of its meaning. My apologies to Mr. Lin.

No, not Pink Floyd’s “The Wall”, but the inventive land artwork called “Whose Land? Whose Art?”. (Photo by Jeff J. Brown)

17) “Digging a Hole in China” ends with a rainbow splash: a six-minute animated movie by the aforementioned Cao Fei (#11 and #12), called “RMB City: A Second Life City Planning” (2007-2010). To see for yourself, here is the YouTube link: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9MhfATPZA0g. Unfortunately, it is of low quality, 240p, so it is very blurry. Its popularity has inspired her to produce a “Making Of” clip, to describe her inspiration and its production: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qi_jrNGa9RM, which is dubbed in English and is higher quality.

Cao and her team ensconced themselves in Second Life, the world’s largest online world, developed by Linden Lab, to build their virtual city together. From a Chinese land use perspective, it is endlessly fascinating. The clip starts by showing a rock and roll drum set perched on China’s flag. The Chinese flag is floating over the whole affair, its main gold star, which represent the Communist Party of China, stuck perpendicularly it the red cloth, while the other four smaller gold stars, symbolizing the four socioeconomic classes, float in the air above.

Below is a crowded, jumbled cityscape island in an infinite sea, dominated by a fire breathing smokestack. A high speed train goes round and round, in midair. The Beijing Olympics’ Bird Nest Stadium is standing in water. Off in the distance, is an iconic statue of a waving Mao Zedong, seeming to topple into the sea. In a shopping cart is a huge Buddha statue, along with skyscrapers. Along with a Pink Floyd-esque Panda bear floating in the air, CCTV’s famous Beijing “Pants Building” is swinging around, upside down, hooked to a crane, while its just as recognizable Shanghai tower, here in pink, looks like it was thrown onto the city pile, as an afterthought. Spinning outside of the city is a giant bicycle wheel, suggesting an historically popular form of personal transportation, now eclipsed by the automobile.

Tiananmen Gate is skirted by water and supported by an expressway pier, with Mao’s famous portrait replaced by a Panda bear. There is a huge Maotai liquor bottle in the center of the city and a Star Wars-esque ship hovering nearby, with a Chinese rocket ship sticking out towards space, while it fires off missiles in all directions.

Also inside the city is a jet airliner juxtaposed with an ancient Chinese junk boat. In the shade of a huge white umbrella dome is the state seal of China, with the Bank of China’s logo in the background. A rotating neon drum is flashing the Chinese symbol for “to mortgage”. Next to it is a pink roofed, pollution shrouded villa development project. It is overshadowed by an ugly industrial plant, and its name is the hilarious send-up, “First Under Heaven Village”. Behind this “urban paradise” is a big orange hard hat and below it is a gigantic Mickey Mouse swimming pool.

Container ships come and leave RMB City’s shores at lightning speed and jets fly every which way. Underneath the city, it is girded with a big sign that screams “HARMONIOUS SOCIETY”. Nightfall arrives, the hypnotic, airy-fairy chime music fades away and the city is still in motion, as everyone is treated to a fireworks display.

The dreamy, hypnotic “RMB City”. (Photo by Jeff J. Brown)

Ms. Cao has done herself a real disservice, by posting such a low quality version of RMB City on the web. The one presented at the art exhibition was high quality and luckily, I took a number of photos of all the changing scenes. Hopefully, the above descriptions will help you parse some of the details, if you watch it.

In any case, it is a fascinating, dazzling, almost hypnotic look at land use in China, with enough symbols and inferences to keep you thinking and reflecting for many days, which is what revolutionary art is all about.

The huge billboard on the side of the exhibition hall, where “Digging a Hole in China” is showing. (Photo by Jeff J. Brown)

After seeing this incredible art exhibit, my wife and I went to a nearby, private gallery, where Western artists were presenting their work. Large plastic models of colorful fruit, drawings of Italian arches and three dimensional, rainbow lacquered metal wall hangings of butterflies, pedestrians and lipstick being put on a mouth were selling for thousands of yuan each. Yaaaawn, boooooring. I’ve already forgotten what they look like. However, I’m still thinking and rethinking all that “Digging a Hole in China” was trying to convey to its visitors, and I’m sure everyone of us who see it will be pondering its many meanings for a long time to come.

Ah, the joys of revolutionary, communist Chinese art – southern style.

Hats off to the exhibition crew, which has done a superb job:

Exhibition: Digging a Hole in China

Where: OCAT Shenzhen, Exhibition Hall A, F2, OCT Loft, Nanshan, Shenzhen, China

When: 2016.3.20-6.26

Admission: free

Curator: Venus Lau

Exhibition Design: Betty Ng

Assistant Curator: Qu Chang

In the future, I suggest that OCAT post its website on their public media, the website of the current exhibition, as well as the email address to contact the group. Herewith,

http://ocat.org.cn/index.php/Exhibition/?aid=384&lang=en

Why and How China works: With a Mirror to Our Own History

JEFF J. BROWN, Editor, China Rising, and Senior Editor & China Correspondent, Dispatch from Beijing, The Greanville Post

Jeff J. Brown is a geopolitical analyst, journalist, lecturer and the author of The China Trilogy. It consists of 44 Days Backpacking in China – The Middle Kingdom in the 21st Century, with the United States, Europe and the Fate of the World in Its Looking Glass (2013); Punto Press released China Rising – Capitalist Roads, Socialist Destinations (2016); and for Badak Merah, Jeff authored China Is Communist, Dammit! – Dawn of the Red Dynasty (2017). As well, he published a textbook, Doctor WriteRead’s Treasure Trove to Great English (2015). Jeff is a Senior Editor & China Correspondent for The Greanville Post, where he keeps a column, Dispatch from Beijing and is a Global Opinion Leader at 21st Century. He also writes a column for The Saker, called the Moscow-Beijing Express. Jeff writes, interviews and podcasts on his own program, China Rising Radio Sinoland, which is also available on YouTube, Stitcher Radio, iTunes, Ivoox and RUvid. Guests have included Ramsey Clark, James Bradley, Moti Nissani, Godfree Roberts, Hiroyuki Hamada, The Saker and many others. [/su_spoiler]

Jeff can be reached at China Rising, je**@br***********.com, Facebook, Twitter, Wechat (Jeff_Brown-44_Days) and Whatsapp: +86-13823544196.

Read it in your language • Lealo en su idioma • Lisez-le dans votre langue • Lies es in deniner Sprache • Прочитайте это на вашем языке • 用你的语言阅读

[google-translator]

Wechat group: search the phone number +8613823544196 or my ID, Jeff_Brown-44_Days, friend request and ask Jeff to join the China Rising Radio Sinoland Wechat group. He will add you as a member, so you can join in the ongoing discussion.

I contribute to

I contribute to